Back to Edinburgh Index

Liberton Kirk Cemetery

Edinburgh, Scotland

Liberton Kirk and its graveyard.

People who know me know that I am a sucker for graveyards when I visit a place. They tell you a lot about the people and the history of the area, not in retrospect but as it was written at the time. So when I arrived in Edinburgh, in the south eastern suburb/village of

Liberton, my first morning's walk was to the nearest graveyard, and it didn't disappoint. I actually paid two short morning visits, but I could have stayed there for a whole week or more. As it was, I spotted more than enough of interest to fill a decent size web page. So here we go.

One of the earliest known sculpted depictions of ploughing

Although I entered the graveyard in complete ignorance of what I might find, I think it appropriate to start this presentation with what is one of its most widely known features.This is one of the earliest known sculpted depictions of ploughing. It shows ploughing and sowing activity against a backdrop of the hills and streetscape of the Edinburgh of the day.

Tabletop grave with ploughing image

The image is on the side of a tabletop grave which would defy the efforts of any bodysnatcher of the day.

Skull & Crossbones

I got a fright when I saw my first skull & crossbones. Was this the grave of a pirate or was it just there to deter others from interfering with the grave. Then I found another and another and I wondered even more about their significance.

They could, of course, be just a momento mori reminding us that death is final, at least for the dead.

On the other hand they have appeared on mass graves of victims of the various plagues through history, though these may be a bit late for that. There is a suggestion that these particular ones may have come down from the nearby site of the Knights Templar (

Rosslyn) via the Freemasons for both of whom the emblem was significant.

There is tremendous variety in the presentations of the emblem both in skull design and accompanying symbols.

Here the terrible twins have survived almost intact.

This one first reminded me of the

Deathshead Moth but I'm sure it is nothing so banal.

This one had no bones and the flesh still on, and was surmounted by a flying crown. Perhaps some member of royalty or the nobility buried alive?

Some of the smaller upright stones were clearly in danger of falling over, or being pushed, from a long time back, possibly at the very beginning, and these were fitted with, a by now much corroded, metal bracket to keep them upright. Clearly that worked.

Celtic Crosses

There are quite a few celtic crosses in the graveyard. It is not clear to whom this one, in nature's fond embrace, belongs.

This teacher of singing has managed to keep his posthumous calling card a little more visible.

And this poor fellow, having survived WWI, died some three months after its end at the age of 27. Might this have been from injuries received during his service or was nature just being a bit more cruel.

And this poor guy didn't even get that far. He fell a year before the war's end and isn't even buried here, just commemorated. He is buried where he fell at Villers, Faucon in France. There are many families who, not having the body at home, have opted to commemorate their fallen dead on family gravestones. At least this man was interred. In my own case, and in many an other like mine, family members who fell were never found and are commemorated in various ways on the home front and on monuments at the war front itself.

This one pulled me up short when I saw the words

Delville Wood. This was the first phase of an allied attack on three woods which were impeding the advance on the Somme in mid 1916. Delville Wood was taken in July but the offensive was not pushed on to the third and last obstacle, High Wood. It was in the attack on High Wood on 16 September 1916 that my uncle John lost his life. You can read about that appaling cock up

here. Tanks my arse.

The graveyard also has a general memorial to those locals who fell in WWI. It was designed by

Pilkington Jackson who is, himself, buried just down the road in Lassewade.

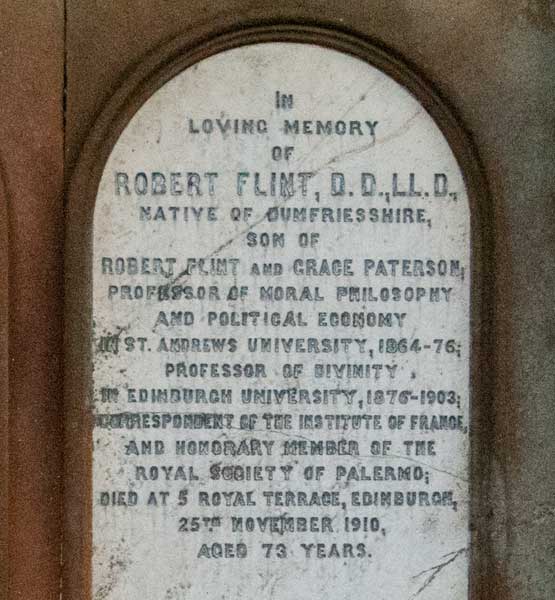

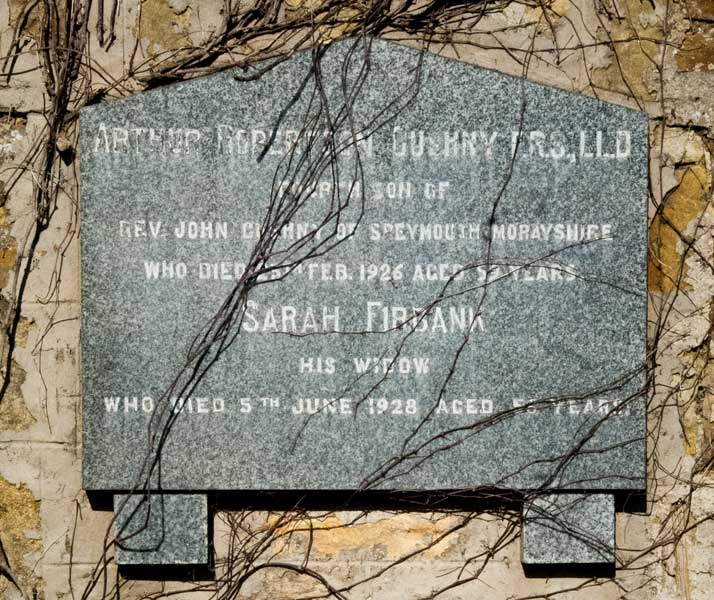

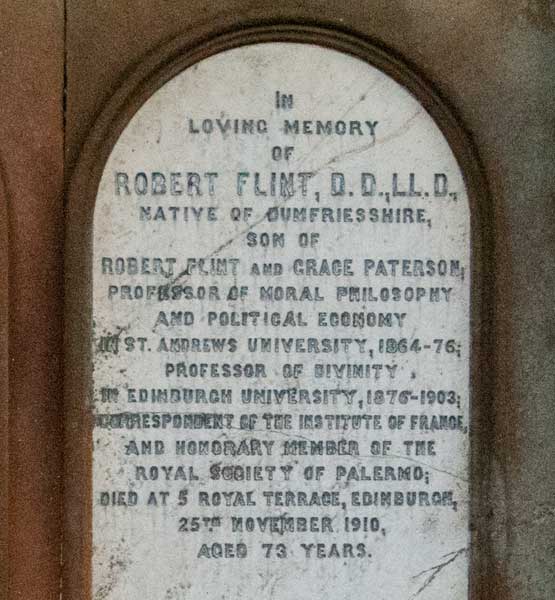

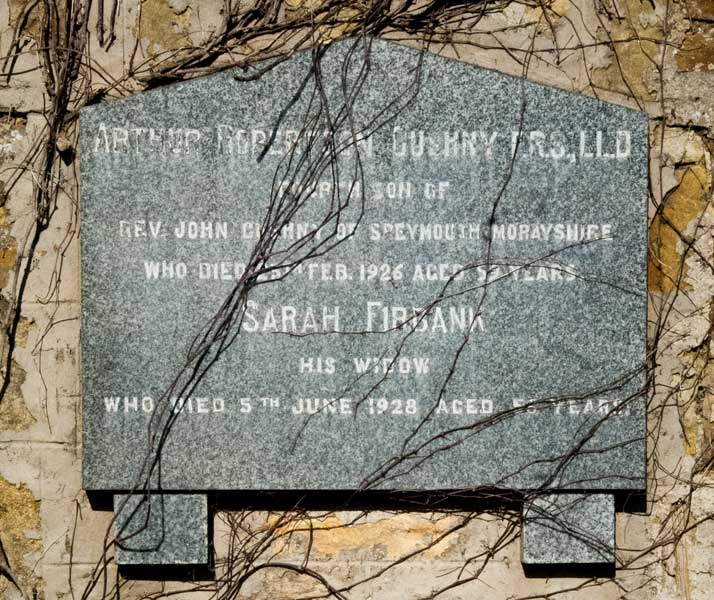

I am always amazed/amused/saddened by the posthumous flaunting of distinctions, honours or academic qualiications. It seems irrelevant by then, and I get the impression that these people equally flaunted their acknowledged importance during their lifetime. Perhaps I do them an injustice, but that's how I feel. I'm all for the simple grave.

This man's qualifications are included, but it is interesting that his main recorded claim to fame, in this graveyard at least, is that he is the son of his father. One assumes that the father must have been a very important person. However, no matter how important he was he would have been eclipsed by his son who, as a pharmacologist and physioligist, carried out ground breaking research in, and changed the course of, some aspects of the medicine of his day. You can read the short version

here or the long version

here.

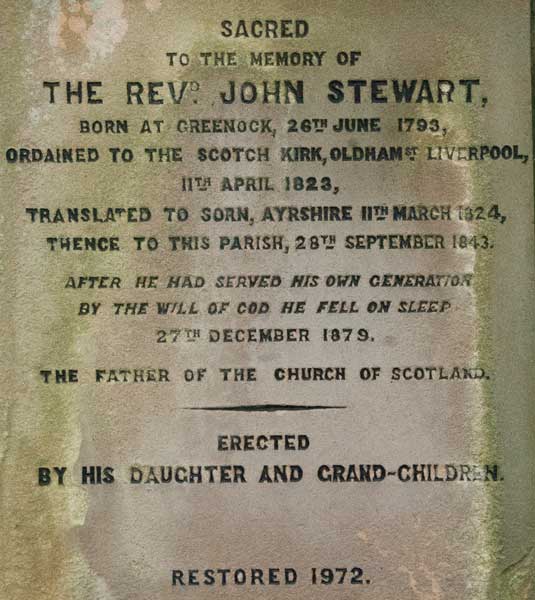

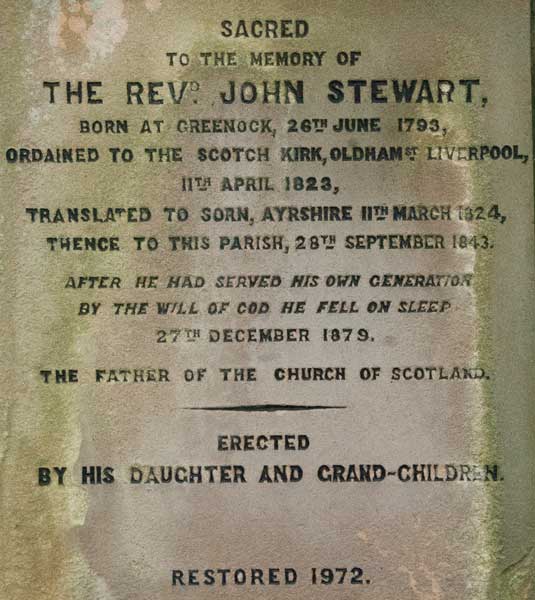

This is a Stewart family grave. Clearly they were very important people, if we go by the size of the stones and enclosure.

John Stewart, in the leftmost panel, is described as The Father of the Church of Scotland. So I thought I had really stumbled on something heavy here. However, when I checked it out, there seem to be multitudinous Fathers of the Church of Scotland and I have come to the conslusion that it is some sort of an honourary title.That this man should be THE one and only seems like the family stretching it a bit.

There is something quietly dignified about this one. A man simply described as an optician but with the sundial tantalisingly suggesting that his interests may have been a little wider than his formal occupation.

I'm told that there is a strong Polish and Chinese presence in the area and, funnily, enough they are the two foreign language graves I spotted. However, my visit was a short one and I didn't do the whole vast cemetery. I was a little surprised to find no trace of Gàidhlig in the cemetery. But my knowledge of the history of this area is non-existent.

And this is the Chinese one.

I saw a few references to falling asleep and I'm never sure what to make of them. It's something I associate with explaining death to children but don't normally expect to find in an adult environment. There are also some unusual items on this grave, including a boot and two meerkats (or ferrets?) with containers.

It would be interesting to know what they are about.

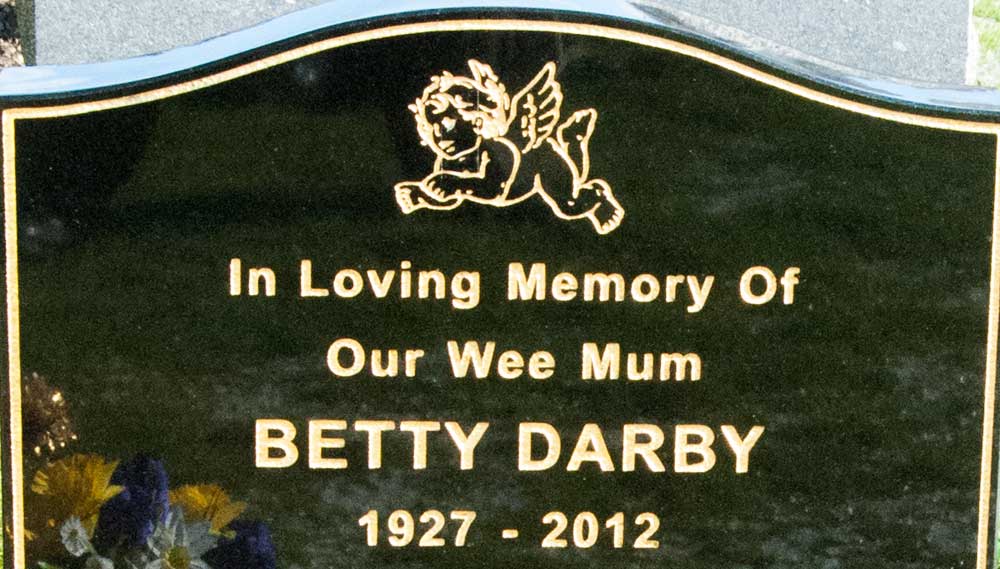

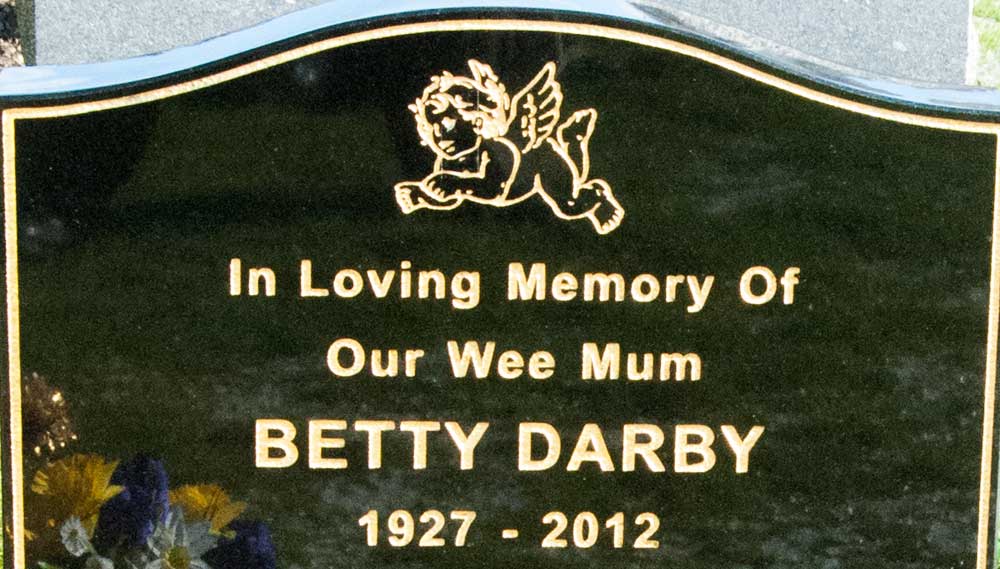

Then there's Our Wee Mum. I know she was 85 and may have lost a bit of substance in old age, but the "wee" is hardly intended to describe her physical stature. I know in the case of wee bairns it is both a physical description and a term of endearment. Presumably here it is only the latter.

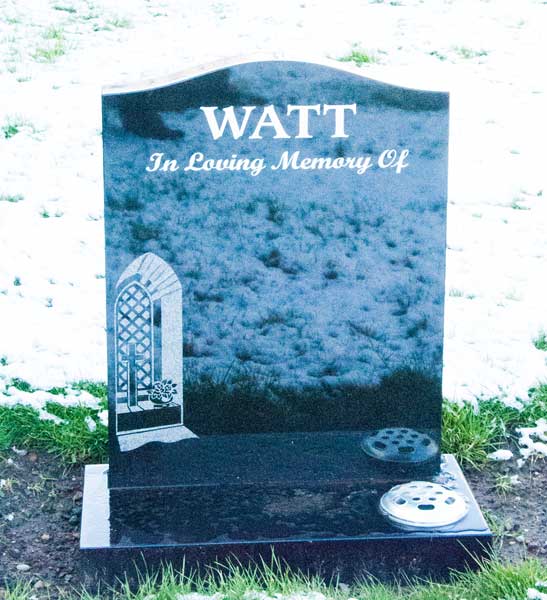

As far as the Watt family is concerned it looks like a case of for whom the bell tolls.

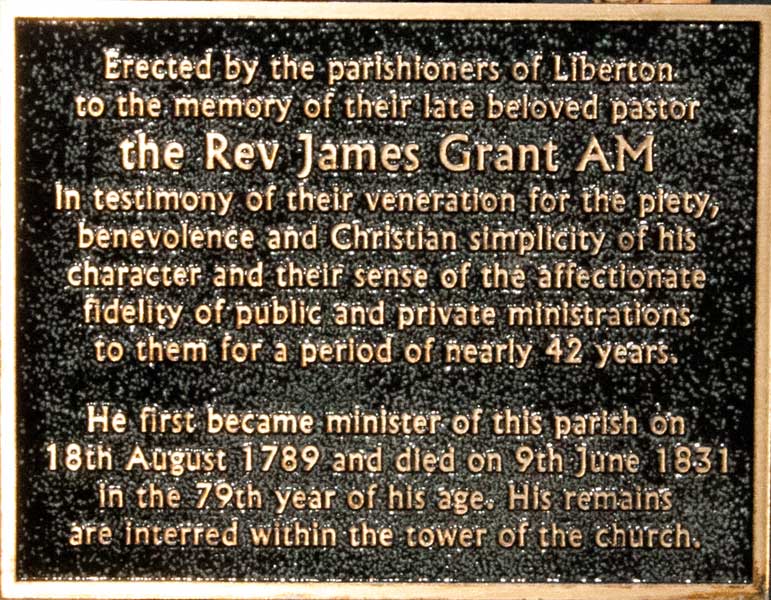

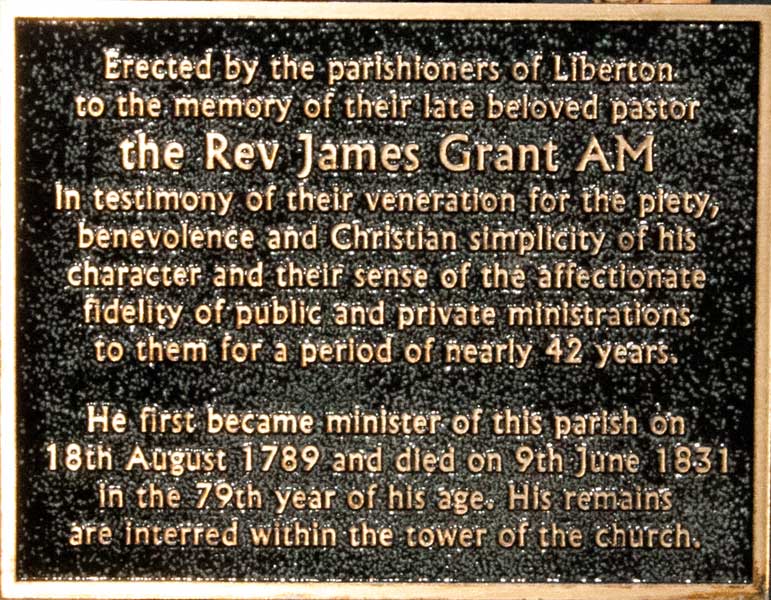

This is a monument to an early pastor of the church, Rev James Grant, ministering from 1789 to 1831. Details below.

There seems to have been quite a bit of vandalism around if one is to put down all the overturned gravestones throughout the cemetery to malice rather than to bad weather.

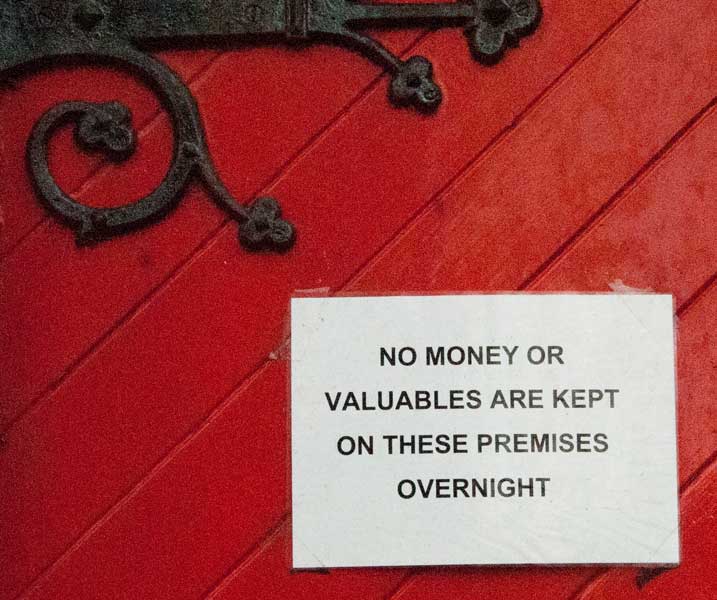

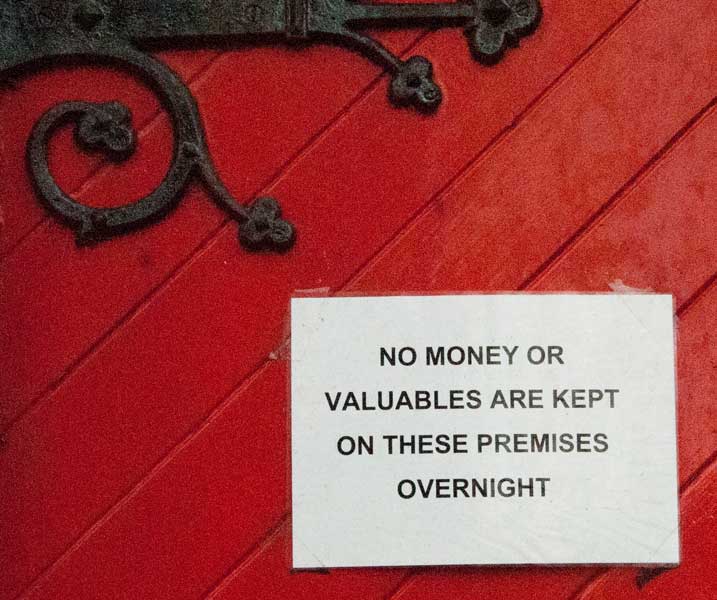

And there are still signs of active crime in the area.

Even the lightning conductor needs a bit of extra protection except, presumably, during a thunder and lightening storm.

I didn't actually have an opportunity to see the inside of the church which I am told is worth a visit. Perhaps an other time.

Liberton Kirk

Back to Edinburgh Index