Back to Polo's home page

Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Cymru

Dinbych - 2001

25 years on

After a 25 year break I was back at the Welsh National Eisteddfod this year. I wasn�t sure what to expect. I had been out of touch with both Welsh culture and politics on the ground but I was aware there had been some changes in the intervening years.On the surface, at least, the language situation had much improved and Wales now had its own parliament, albeit with fairly restricted powers compared with the aspirations of the nationalist and language movements of the 1970s.

My general impression after a week at the Eisteddfod was that despite the changes, the underlying issues remain the same as in the 1970s, except that Wales itself now has the responsibility and the capacity to deal with them - it is now a question of �Welsh Will� rather than �UK Won�t�.

Eisteddfod is the pinnacle of Welsh culture

The Eisteddfod (meaning �session�) is the pinnacle of Welsh speaking culture. [1] It is an annual event and covers an unbelievably wide range of activities. Cultural competitions play a very large part but the occasion is used by various associations and societies, political parties, government-backed organisations and institutions, commercial organisations and producers, craft workers, churches and the media, to put a case, sell a product or just reassure the general public that they are still in the land of the living.

Attendance

Attendance at the week-long festival is

between 150,000 and 200,000 visitor-days.[2]

Denbigh itself is a very pretty town. It

is situated on a hill and is dominated by a castle which is still in very good

condition. The town centre boasts an old stocks which, thankfully, was not in

use during our stay at the Eisteddfod this year.

Although it actually means a �throne� or

�mound� the word Gorsedd is used as a

collective noun for the assembly of druids and bards when they gather in their

colourful garb to oversee the awarding of the crown, chair or prose medal,

initiate new members into the fold or welcome the delegates from the other

Celtic countries to the Eisteddfod.

There is intense local involvement in the

Eisteddfod, both in the two year run up to the festival and in making a success

of it on the day. Police and local authorities are involved in planning traffic

flows, as Eisteddfod locations are not initially suitable for the vast influx

of visitor cars, busses and supply trucks during the festival. In Denbigh the

police ran a very well thought out one-way system which proved its worth during

the week. Many of the shops and public buildings had staged window and interior

exhibitions recalling the town�s involvement with previous national and local

eisteddfodau.

Special groupings from Denbigh and the

surrounding area were formed for the festival and these performed in the

evenings in the pavilion during the week. They included a cast of 200 primary

school pupils who put on a light music show; a 160 strong cast from the local

area secondary schools who staged the musical Oliver and an almost 400 strong

Eisteddfod mixed voice choir which participated in a miscellany entitled �Viva

Verdi� with nationally renowned Welsh solo opera singers.

Other existing groupings, not

specifically formed for the occasion, but appearing in evening concerts in the Pavilion, included the Welsh Youth

Orchestra, the Cardiff Bay Orchestra, the Ruthin mixed voice choir and a number

of area-based male voice choirs. The internationally renowned Welsh bass

baritone, Bryn Terfel, was also a major attraction at one of the evening

performances.

During Eisteddfod week itself special precautions were in place. Cars were

inspected for mud on arrival at the field and clean cars were certified as

having arrived in that condition. Local mud, subsequently picked up during the

week, was deemed to be �clean mud�. Local farms were put out of bounds to

visitors and cars arriving with pets on board were turned away. At the time of

this writing, the precautions seem to have paid off and the only perceptible

adverse effect was a modest reduction in attendance figures.

However, the decline of the coal and

steel industries in the southern valleys, combined with a generation gap between

the traditional forms of entertainment and the modern TV and cyber world, has

led to a significant reduction in entries for the male voice choir competition.

In the past, intense local rivalries led to a high level of entries and

cut-throat competition. This has now given way to the lure of US tours. There

is a fear that, once having won the competition, risking lower placings in

subsequent years could tarnish the image required to market the choir abroad

and maximise tour takings. While this attitude is understandable, it runs the

risk of eventually undermining the future of that competition.

Most Eisteddfodau become memorable for

one reason or another.

The Ruthin Eisteddfod in 1973, held not

far from Denbigh, was memorable for Alan Lloyd Roberts winning both major

poetry prizes, the crown and the chair, at the same Eisteddfod. It is not

unusual for poets to have won both crown and chair, even many times over, but

to win both at the one Eisteddfod is relatively rare. [4]

The authorities were very lucky that year

to have had two poems which the adjudicators had already indicated, in their

written adjudications, were worthy of a chair. In fact Dic�s poem only pipped

Alan�s by a short head. In what subsequently turned out to be ironic, one of

the adjudicators had unwittingly commented that Dic's winning poem (Spring)

"was in the same class as Dic Jones�s (Harvest)" which won Dic the

chair ten years previously.

The double (crown and chair) was pulled off again the following year in Wrexham and in 1980 in Diffryn Lliw by Donald Evans and had not been repeated since.

So what did this year hold in store that

would make it memorable. The Denbigh Eisteddfod was going to be historic

anyhow. The modern (post 1880) Eisteddfod had visited Denbigh twice before, in

1882 and 1939. On neither occasion was a chair awarded. In 1939 neither chair

nor crown was awarded, the first time this had happened in the history of the

Eisteddfod.[6] If neither was awarded this year, history would repeat itself. If

only the crown was awarded then Denbigh would have refused to chair a bard

three times in a row, and if a chair was awarded the Denbigh jinx would be

broken. A no-lose situation for those wanting a piece of history, but which

would it be?

Great effort goes into maintaining the

standard of entries for competitions. Prizes are not awarded lightly.

Irrespective of the importance of the competition, if the standard of entries

is not judged adequate no prize is awarded. Since 1880 the chair has been

withheld on 14 occasions and the crown on 4 occasions. The Prose medal has been

withheld 11 times since its inception in 1937.

While the entrants strive for perfection,

its absence does not necessarily deny them the prize. For example, the

adjudicator in one of this year�s main literary competitions criticised the

leading entry and suggested some faults that might be remedied, yet the prize

was awarded. The adjudicators are well aware of the need to encourage new

writers and will strive to award the

prize, providing standards are not compromised. This constructive approach was

vindicated when one of this year's winners subsequently revealed that, were it

not for the encouragement of an adjudicator at an earlier National

Eisteddfod, they would not have had the

confidence to persist.

The competition for the prose medal (a prose

volume of under 40,000 words) had �voices� as its subject. The winning entry

dealt with the tragic loss of an only daughter in a car accident, the effect on

the father who cut himself off from all human and other contact, except for the

voices which challenge and torment him to his limits. We see his despair and

frustration, his anger and rage, his desire for vengeance and his

self-reproach. We follow his attempted suicide and share his rock-bottom

before the tentative signs appear of his coming to terms with himself and

opting to rejoin the living.

The winner was Elfyn Pritchard, from Gwyddelwern

(Swamp of the Gael) near Bala. He already has a distinguished career as a

novelist and has adjudicated at a number of National Eisteddfodau. While his

composition is not based on direct personal experience, he makes the point that

everyone suffers losses in their life and as a teacher, headmaster and deacon

he has also shared in the losses of others.

The winner was Penri Roberts of

Llanidloes. He is the headmaster of a primary school in Newtown and is to be

the head of Powys�s (north-east Wales) first Welsh School from September.

This had also been the subject for the

crown competition in 1972 and at that time the winning poem examined

contemporary Welsh problems, drawing on the Mabinogion tale of Branwen,

Matholwch, the Irish and the �cauldron of rebirth.

This year�s winning entry was more

intensely personal. It dealt with the initial fulfillment of a maiden through

the birth of her baby and her subsequent despair at the baby�s death. She was

then �neither maiden nor mother�. It finishes with her realisation that,

despite what happens to us, we still have the power of choice - to choose living over despair. This is the

�rebirth�. In his adjudication, Dic Jones confessed to being �completely

floored by the section dealing with the pregnancy, birth and mourning�.

Secrets are hard to keep, particularly in

a close community like that of Welsh Wales, where everyone either knows

everyone else, or at least knows someone else who does. There was a great air

of expectancy building up around this competition during the week (some would

say for the previous month). Rumour had it that something big was going to

happen and everyone wanted to be there. The BBC was finding it hard to line up

people for a live studio discussion during the event. For once, no one wanted

to be part of the chattering class, commenting on history as it passed them by.

They wanted to be part of its making.

This year the winner was a woman, we were

part of history and the enthusiasm of the crowd knew no bounds. Pure magic.

Hwyl.

She revealed that she had already entered

this competition some years ago, and would not have done so again, were it not

for the encouragement of the adjudicator who spotted her potential. When

journalists pressed her for more details she referred them to previous

published volumes of adjudications with the clue that her pen-name then had not

been much different from the one she used this year. She clearly felt that journalists

should do a little more of their own research rather than having stories handed

to them on a plate.

The winner was Menna Medi, from near

Caernarfon, who has just left BBC Radio Cymru after 15 years as a researcher,

producer and presenter, to become Chief Marketing Officer for the Sain

Recording Company.

The Gorsedd remained a separate

organisation from the Eisteddfod until 1937 when the two united in the National

Eisteddfod Council, now the Court of the National Eisteddfod.

The Gorsedd assembles, in costume, five

times during the Eisteddfod. In the pavilion it oversees the presentation of

the results of the three main literary competitions - crown and chair for

poetry and medal for prose - and at the Gorsedd circle, weather permitting, it

meets twice to welcome newcomers into its ranks.

A group of young girls from the local

primary schools perform a flower dance - symbolising the harvesting of the

flowers of the field to be offered to the Archdruid in a gesture of welcome.

The dance was choreographed by Cynan, a former Archdruid, who did much to

embellish and tighten up the ceremonies into their modern day format. The

Gorsedd is welcomed to the area twice-over: a local mother presents the Hirlas

Horn - symbolising the wine of welcome; and a local maiden presents the Blodeuged (or bouquet) - symbolising the

fruits of the land and the land itself. All this is done with dignity and to

the accompaniment of harp music.

Apart from being impressive, this is all

great fun, and Archdruids, being men of considerable literary accomplishment and wit, add spice with their off

the cuff remarks, sometimes bringing the house down.

Up to this year, the Archdruid, whose

term runs for three years, was elected by the 30 member Gorsedd Board. This

Board consists of the serving Archdruid, his Deputy, former Archdruids, about

10 other officers and a dozen or so �ordinary� members. By contrast, the total

membership of the Gorsedd is almost 1,700.

Following strong pressure to democratise

the procedure, and various meetings of appropriate sub-committees, it was

decided (conceded) that every member of the Gorsedd should be entitled to a

vote in the election. Any member can now propose a candidate subject to finding

a seconder and five other supporters.

In a letter to the Western Mail[8], early last year, former Herald Bard, Dillwyn Miles, challenged

Lewis�s assertion that the Prince of Wales hadn�t a drop of Welsh blood in his

veins. In a passage reminiscent of the opening paragraphs of St. Lukes gospel,

Dillwyn took the reader on a tour of the Prince�s lineage and managed the

staggering feat of ending up with Owain Glyndwr. Glyndwr was one of last of the Welsh leaders to rebel against

English rule in Wales at the beginning of the 15th century.

Dillwyn is worthy of mention in his own

rite. A member of the Gorsedd since 1936 and Herald Bard since 1966, he was one

of the �characters� in the Gorsedd. He stood out, in what was already fairly impressive pageantry, with a Herald Bard regalia designed by the former Archdruid, Cynan. This gear was reminiscent of Lawrence of Arabia and evocative of Dillwyn's wartime service in the Middle East. It was, however, a bit over the top and Dillwyn abandoned it in favour of his normal druid's white robes shortly after Cynan's death in 1970.

Each group is presented to the Archdruid in turn and

delivers a message, in their own Celtic language, from the home country to a

packed pavilion[9]. This year�s

ceremony benefitted from a welcome innovation decided on last year - a Welsh

translation of the message was displayed on the two giant screens on either

side of the stage. Ireland�s delegates were Muiris � R�ch�in and Bl�thnaid �

Br�daigh.

Two Irish residents, who had died, were

remembered this year: an tAthair Diarmuid � Laoghaire, SJ, whose Gorsedd name was Bendigeid Fran, son

of Llyr in the Welsh myth of the Mabinogion (on the Irish side of the mythology

this would be Bran son of Lir); and Alan Heussaf, a Breton well known in Irish

language circles, whose Gorsedd name was Gwenerzh [Venus or the Muse?].

The Welsh party seem to have constituted

the entire audience at the accordion competitions but were impressed at the

general range of activities and the �tremendous efforts being made to foster

the language and traditions of the Emerald Isle�. The Archdruid commented on

efforts to improve the links between Ireland and Wales and felt that these

reciprocal visits provided an opportunity to discuss the comparative state

of language and culture in the two

countries.

The Oireachtas had a stand on the

Eisteddfod field at a number of Eisteddfodau in the early 1970s. The one in Ruthin in 1973 attracted considerable interest. This seems to have been a cultural abberration, however, and has not been repeated.

The stand promoted a range of Irish publications, and members of Craobh M�ibh�

provided live upbeat versions of traditional Irish music. Rosc, Conradh na

Gaeilge�s bilingual monthly, carried a

trilingual �front page� specially directed at those attending that Eisteddfod.

Virtually all of the formal Eisteddfod

activities take place on the field.

The centrepiece of the field is the giant pavilion

which accommodates 4,000 people, comfortably seated, along with a vast stage

area and a network of service buildings including offices, dressing rooms, hospitality,

press room and the ever necessary loos. The Eisteddfod has a permanent national

logo, and individual logos for each annual event, but the real logo for regular

attendees is the pavilion itself. It dominates the field and is a sort of

trademark for the festival.

The pavilion used to be a wooden

structure, but by the mid 1970s this was on its last legs and, after much

dithering and controversy a flashy new steel basedstructure was acquired. This turned out to be uneconomical to

move around the country and was finally abandoned. The current structure, which

is hired out each year, is, in fact a circus tent but it too is now reaching

the end of its working life.

As in the mid 1970s the future of the

pavilion is, once more, at the centre of heated discussion. The current

structure has served the event well, but the canvas flaps in the wind and

resonates to the rain. This makes it unsuitable for some of the competitions

and, in particular, for the world class stage performances in the evenings. All

options for renewal are under consideration but time is running out.

The bulk of the stands consist of

wooden-framed, canvass covered, stalls and most of the ordinary commercial

interests, voluntary groups, political parties, churches and the like were

housed in these. The majority were vibrant centres of information, propaganda,

controversy and fun but some were as dull as ditchwater with a table, a few

posters and a few down-at-heel aging volunteers. Many housed small outlets for

arts and craft workers whose products caught the eye and were, on the whole,

modestly priced. Some catered for a broad range of interests while others were

more narrowly focussed. These latter included the political parties, churches

and voluntary organisations.

There was entertainment aplenty, and

particularly for children. Otherwise, families, whom the festival wants to

attract, could have had a rawer deal if they were relying on some of the more

staid stalls around the field.

The company was formed by Idris Charles, a vibrant Welsh entrepreneur with a

background too colourful and varied to recount here. It promotes new young

Welsh artists and many of these were performing live on the field. Robin Jones

had been �discovered� on the TV programme �Star for a Night�. He was deluged

with offers from all over the UK but has decided to continue singing and

songwriting in Welsh and signed up with Penffordd. He is a personable young man with a very lyrical voice and his

first CD is mainly of his own compositions with a beautifully rendered

traditional number (Mari fach fy nghariad) and a tribute to the Welsh leader

Owain Glyndwr for which he wrote the melody and his father the words.

The contest got lots of advance

publicity. The Liverpool Daily Post pointed out that the Tory contestant could

not sing and was going to recite a poem instead. There may be the germ of a new

Eisteddfod poetry competition here!

Postwatch, the Post Office consumer

watchdog, were offering participation in a raffle for £50 to those who could

identify the locations in Wales of six post office fronts from a set of

photographs. There was a deterministic solution for those with microscopic

vision. I settled for taking off my glasses and am very hopeful of a cheque in

the post.

In one instance, a glass perspex case

gave the impression that the exhibit it normally housed had been stolen or taken away for cleaning or repair. On closer

inspection it was found to house a grain of wheat and a spent .22 cartridge.

The accompanying plaque said it was �untitled�. �Foot �n Mouth� sprang

immediately to mind.

The selectors in the architecture

category were happy that the range of entries bore witness to architecture in

Wales heeding the call for responsible development. There was a little irony to

this competition, however. On the one hand, the gold medal was won for a

building that was explicitly advertised

as not using cement, while, on the other, the German based multinational Castle

Cement was underlining its support for Welsh culture by sponsoring the first day

of the Eisteddfod. It also stretched a point by claiming to underpin democracy

in the Celtic lands by using Welsh cement in the construction of the Scottish

Parliament building in Edinburgh.

The Eisteddfod�s position on the use of

Welsh can be summarised as follows:

Apart from the fixed interpretation

infrastructure, the small portable cabin setup, and the even lighter single

pole structure used in the press room proved extremely efficient for small

meetings. They are an example of how modern technology can facilitate

bilingualism and are relevant to other minority language situations beyond

Wales.

The experiment was pronounced a success

at last year�s annual meeting of the Eisteddfod Court and maes B is now to become a permanent feature of the

Eisteddfod.

Activities on the maes B in previous

years had been organised by the Welsh Language Society but this year the

Eisteddfod refused to continue the arrangement as long as the Society was

involved in protests on the main field, particularly the defacement of some of

the stands. The Society retaliated by

organising its own gigs in the area generally. Despite the opposition to what

some see as an establishment take-over, the maes B looks set for a long

innings.

In view of the rising controversy over

English speaking immigration into Welsh speaking areas, speakers were very

careful to completely disassociate the Society from the UK British National

Party which had planned a large rally on the subject in Llanerfyl during the same week. Nevertheless, one of the

tabloids managed to find a Rabbi and his wife at the festival and elicit quotes

on �beginnings of Nazism referring to protests on the field. The paper

concerned was generally taken to be the one referred to in the Executive

Committee President�s speech as a �faked-Welsh daily rag�.

Many of the issues involved in this area

are the subject of bitter controversy in the media and among the political

parties. Preserving and developing what is a minority language (c 20%) in any

society raises issues of community, positive discrimination and, inevitably,

immigration.

The four main political parties in Wales

(Plaid Cymru, Labour, Liberal Democrats and Conservatives) have stands on the

field.

While Wales has changed a lot since the

mid 1970s in terms of official status for the language and significant

devolution from Westminster, there is still a strong protest movement and some

of the political parties are divided down the middle on the critical issues of

community development in the current linguistic context.

The Cymdeithas�s four poster bed saga

gives a broad idea of what is involved. The posters read �There is no need for a new Welsh language

act�, �There is no need for a property act�, �The struggle is over�, �National

Assembly, go back to sleep�.

The principal difference I notice from

the 1970s in this area is how these issues, considered by many in those days to

be fringe issues, have now moved very much to centre stage. Plaid Cymru and the

Labour Party have both published documents dealing with the language and

housing issues. But the most interesting development was the migration of these

issues onto the Eisteddfod stage itself during the week.

On the Tuesday, the flames were further

fanned by an article in Barn, a Welsh language monthly, where the former head

of the Welsh Language Board, John Elfed Jones, a man with a distinguished

business career spanning over forty years, compared immigration from English

speaking areas into (Welsh speaking) rural Wales with the foot and mouth epidemic. Nothing was being done

about the former while all the nation�s resources had been mobilised to combat

the latter. He bemoaned the higher priority given to flocks over culture and

herds over a way of life. (The preceding sentence is taken from a translation

of his article provided by the Western Mail and it does less than justice to

the resonance of the original Welsh phrases[11]

On the Wednesday, Plaid Cymru Vice

President, Gwilym ap Ioan, had to stand down from the party�s national

Executive after claiming Wales had become a dumping ground for England�s

oddballs, social misfits and dropouts. He actually compared Wales in a British

context with Montana is the US. This in turn led to protests on behalf of

Montana.

On the Thursday, the Chairman of the

Eisteddfod Council, in his address to the Court, called on the National

Assembly to establish an independent commission to investigate the causes of

the crisis in the rural communities where the Welsh language was in decline and

to recommend, within a year, measures to safeguard these communities. This was

upping the ante from his report of the previous year where he simply called for

a review of some of the Eisteddfod competitions which were not attracting

sufficient entries.

There is a special stand for learners on

the field. This offers basic Welsh classes, advice on learning the language,

Welsh on the web and so on. Some public representatives participate in the

stand�s activities. This year the Chief Constable of Gwynedd (North West Wales)

was awarded his GCSE A level certificate in Welsh as a second language. It was

a condition of his appointment as Chief Constable that he learn Welsh. He

commented that he could do his job perfectly well without speaking a word of

Welsh but it would not be right. He is a strong supporter of Welsh in the force

and appealed for recognition of the resource costs involved in having the force

operate in a second language. These include the employment of tutors and the

need to take on sufficient staff to cover for those on training courses. His

own learning involved several week-long courses at the National Language Centre

at Nant Gwrtheyrn but he now avails of the full-time tutor at police HQ

There are special live viewings of the

Crowning and Chairing ceremonies in the learners stand with a Welsh language

commentary tailored for learners.

In general the Welsh are very patient

with learners (at least in my experience) and they avoid the purist attitude

which has deterred many a shy learner of Irish from trying out their newly

acquired phrases in public.

This was continued this year and the site

carried limited postings about the winners of the main competitions,

information on the Gorsedd and items on some of the sponsors. There is still a

lot of scope for expanding this service. It would, however, need a full time

webmaster, particularly during the festival week. It would also require

sponsorship as resources are very tightly stretched. Any development of the

site would also need to be synchronised with the extensive existing media

coverage of the festival, both on the airwaves and over the internet.

At present S4C (www.s4c.co.uk

), the Welsh language TV channel, relays live TV coverage of the main

ceremonies, events, and competitions from the pavilion. It relays about 30 hours

of analogue and 100 hours of digital TV coverage during the festival. While

this level of coverage is very welcome and a great boon to those not able to be

physically present at the festival, it does have its downside. Those who can

follow all the main events of the festival in the comfort of their own homes

may be less likely to attend the Eisteddfod. In his address, Efion Lloyd Jones

also touched on this, when he pointed out that comparing annual attendance

figures, in these circumstances, is a

worthless obsession, and the press and media would do well to realise the

fact�. Nevertheless, a minimum physical attendance is required each

year to ensure the continuation of the festival. The authorities are therefore

constantly trying to strike a balance between attendance, viewership and the

level of fees charged to the broadcasting companies.

BBC Cymru (www.bbc.co.uk/cymru), Welsh language

radio, has live coverage of most of the major events and much of the rest

of the Pavilion activity. It also carries, on its own website, Eisteddfod news

stories, including informed pieces on the winners of the main competitions, and

a daily diary posting from the field, along with general information and

timetables.

BBC Wales ( www.bbc.co.uk/wales ), the corporation�s English

language radio channel in Wales, broadcasts evening roundups of the days

events on the field and carries general news stories on the festival.

This year, for the first time, the

Eisteddfod installed a computer with an Internet connection in the press tent.

This greatly facilitated the daily diary posting from the field to the Celtic

Cafe website ( www.celticcafe.com ).

These postings are intended to be turned into an illustrated feature on this

year�s Eisteddfod. This will, hopefully, not only broaden the Celtic coverage

of the site, which is largely confined to things Irish, but also introduce the

Eisteddfod to a new overseas audience.

The Welsh Development Authority (WDA)

launched a £1 million Information Technology Trailer as part of the �Wales

Information Society� (WIS) programme. The programme is cofunded by the WDA and

the EU. The purpose-built technology trailer, the largest in Europe, is equipped

with every type of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and it will

travel around Wales introducing the latest technology to the remotest parts of

the country. Rosemary O�Connor, the Director of WIS, has a background in

delivering ICT programmes to small business and, prior to working in Wales, she

managed the Shannon Region�s Information Society and Action Plan.

One of the facilities on show in the

trailer is � www.BestofRuralWales.com

�. This is a rapidly expanding database cum catalogue designed to encourage

small businesses and artisans to market their products online.

The launch at an Eisteddfod was

particularly appropriate as the festival itself is strenuously seeking lottery

funding to finance a new pavilion. They were turned down for first round

funding but are persisting into the second round. Even the druids are looking

for lottery funding to replace some of the

druidic and bardic regalia.

Sponsorship has always been a source of

income for the festival. Last year�s annual meeting noted that some of the companies which traditionally supported

the Eisteddfod were in trouble and a Sponsorship Committee was established to

find new sponsors. It was also decided to set up a sponsors� stand on the field

to publicise individual sponsors. Sponsorship of individual events is also

prominently acknowledged in the Eisteddfod programme (a very well produced

comprehensive manual on the week�s events for a mere £5).

Even the best of sponsorship can bring

its own headaches as the BAE problems outlined above testify. The festival�s

Director, Elfed Roberts, rightly commented that they could not hold an

inquisition on every company which offered them sponsorship and that those

companies which did contribute were often significant employers in Wales.

Nevertheless, in an age where the Government is proclaiming an ethical foreign

policy and anti-globalisation protest is all the rage, the festival will have

to pay more attention to selecting its sponsors if it wants to ensure trouble

free events in the future.

There are also individual overseas

interests represented in the stands, such as the Welsh section of the US

University of Rio from Ohio.

There is also a third world presence, and

connections, on the field. This year�s offerings included the Cymru Cuba

solidarity campaign, the Wales Nicaragua solidarity campaign, a Wales/Lesotho

stand, and an international campaign to counter the global water crisis.

The Burkina party was introduced to the

media, and the public at large, by Ffred Ffransis, a prominent and longstanding

member of the Welsh Language Society. Ffred will be fasting outside the

National Assembly for a week in the lead up to Glyndwr day (16 September), in

support of the Society�s demands. There is pressure building up in some

quarters to have the day declared a national holiday in Wales and the National

Assembly has now agreed to fly Glyndwr�s flag over the Assembly building on

that day.

The settlement itself is a remarkable

story. It originated in the 1860s as part of the migrations to the New World.

These were both economic migrants and �political� refugees. The initial Welsh

group were aware of the extent to which earlier migrants, from various countries,

had been absorbed into their newly adopted societies and they determined to

find somewhere to set up a community which could retain its original values and

language. With help from some American Welsh, and following successful

negotiations with the Government of Argentina which exercised sovereignty over

the area, they chose Patagonia, �a sparsely inhabited territory which had

rejected previous attempts of European settlement�.

The eulogy, which accompanied the

bestowing of the �World-wide Welsh Award 2001� on this expatriate community at

this year�s Eisteddfod, is worth quoting:

Technical

progress was accompanied by social organization, and indeed depended upon it.

The Welsh gave themselves their own government, including a constitution that

did not discriminate between the sexes and provided for voting by secret

ballot, while in Wales farmers were thrown out of their farms for voting

according to their conscience. They set up their own schools, where every

subject was taught in Welsh - while their brethren in Wales were subject to the

indignity of the �Welsh Not�. They founded their own chapels They developed a

very successful commercial enterprise in the form of one of the first

cooperatives to be organized in Argentina, which eventually grew to the extent

of having its own ships. Economic activity led to the building of one of the

earliest railroads in Argentina. They explored the land and eventually

established a �branch� settlement at the foot of the Andes mountains. They

enjoyed their culture, including an annual eisteddfod which continues to be

held to this day and will play host to a Gorsedd delegation this Fall. Also

worth noting are the exemplary relations the Welsh enjoyed with the natives, who

were nomadic, and who they respected as brethren.�

It is not surprising, then, that this

community still retains a special place in Welsh hearts and culture today.

Patagonian Welsh are frequently honoured by being invited to join the Gorsedd

and one particular Archdruid (Bryn � 1975/78), while born in Wales, was raised

in Patagonia, won his first chair at a Patagonian Eisteddfod, and admitted to

thinking first in Spanish rather than Welsh.

There was a rumour last year that

Liverpool intended to invite a future Eisteddfod to that city. This is very

unlikely to happen as Liverpool is not in Wales. The Eisteddfod has been held

outside Wales, but not since 1929. [13] That was in Liverpool, but times have changed.

At the end of the 1950s Liverpool became the focus of Welsh language

and community protests as Tryweryn Valley, near Bala, the home of a small Welsh

speaking community, was flooded to build a reservoir to provide water for the

city. The language protests were bitterly resented by an uncomprehending

Liverpool population while the valley became a rallying cry for a wide spectrum

of Welsh language opinion. It is claimed that it fueled the campaign for

devolution, only now being implemented in Wales, and efforts are still ongoing

to have a fitting memorial erected in

the valley.

The matter came up at last year�s annual

meeting of the Eisteddfod, where Robyn Lewis, now Archdruid elect, pointed out

that in view of the history of Tryweryn, any decision to bring the Eisteddfod

to Liverpool would need the unanimous backing of the Eisteddfod Court.

Harri Pritchard Jones: a Welshman who was

once a GP on the Aran Islands and who in the 1970s when I last met him was

something of a media and cultural personality. He was one of the adjudicators

for the Prose Medal at this year�s Eisteddfod.

Gwyn Erfyl: (reverend) who came to

Ireland with HTV in the 1970s to make TV programmes. Gwyn preached the sermon

at the Sunday morning service in the Pavilion.

Clive Betts: reporter with the Western

Mail. Clive published his seminal book �Culture in Crisis - the future of the

Welsh language� in 1976. The central thesis of the book was the need to protect

the language in the heartland, precisely that theme which Eifion Lloyd Jones

took up in his rousing speech from the pavilion stage on the Saturday.

Meic Stevens: a first class folk singer.

Meic has seen and done it all and come out the other end a sane and very

unpretentious guy. He is nearly finished his autobiography and, by all

accounts, there are many included in it who hope it stays unfinished.

J�ms Nicolas (no relation to Jams

O�Donnell in An B�al Bocht�) former Archdruid and now Gorsedd Recorder. It was

he who read from the stage the list of Gorsedd members who had died during the

year.

It was also a time for memories of those

no longer with us:

Donnchadh O�Suilleabh�in: former General

Secretary of the Oireachtas and delegate to the Gorsedd. Donnchadh was

responsible for the Oireachtas stand at the Eisteddfod in the early 1970s.

Diarmuid O�Laoghaire, SJ, and Alan

Heussaf: referred to earlier.

It was a little ironic that this followed

the relaxing of the condition that the Archdruid must be elected from among

crown and chair winners only. For the last few years, prose medal winners also

qualified as candidates and one of these was elected Archdruid at this year�s

Gorsedd AGM. There are now 11 women winners in these three categories, who, in

theory at least, are potential candidates. The opening up of the electoral

college to the full Gorsedd membership of 1,700 should also help women�s

chances. The reported 700 returned ballots in this year�s election show that

the membership take the process seriously. Let�s see what happens in three

years time when the next election is due.

The adjudicator's comments are no less worthy of mention:

Some red herring!

The real question is how robust is the

heartland as a source of inspiration and sustenance for Welsh Wales, and will

this Wales succeed in achieving peaceful coexistence with its English speaking

fellow citizens.

I look forward to seeing more progress,

and having more fun, on a future visit to the Aladdin�s cave that is the

National Eisteddfod of Wales.

[2] This includes repeat visits by regular attenders. Numbers have

declined somewhat over the years, though they have now stabilised. Attendance

in individual years can reflect particular factors such as the location of the

event, or, as this year, the inhibiting influence of the foot and mouth

epidemic. A significant percentage of the attendance is from the 15 to 25 year

age cohort.

[3] "The circle consists

of twelve stone pillars, sometimes hewn from a local quarry, sometimes gathered

from the fields, or brought down from the surrounding hills. A large, flat-topped stone, known as the

Maen Llog (the Logan Stone), lies at the centre of the circle and provides a

platform from which the Archdruid conducts the proceedings. Facing it, at the

east cardinal point, is Maen y Cyfamod (the Stone of the Covenant), at which

the Herald Bard stands, and behind this are Meini'r Porth (the Portal Stones) which

are guarded by purple-robed Eisteddfod officials. The portal stone to the right of the entrance points to sunrise

at midsummer day, while that to the left indicates the rising sun at midwinter. The shadows thrown by these three stones form the pattern /|\ symbolising the ineffable name and signifying the rays of

the divine attributes�love, justice and truth." (The Royal National

Eisteddfod of Wales� Dillwyn Miles (1978) p136)

[4] In the history of

the modern Eisteddfod (since 1880) this had only happened twice before, in Wrecsam in 1912 and in

Bangor in 1915.

[5] He is shown as the winner in the official book of compositions and

adjudications, published on the day of the chairing. Although this was

corrected in subsequent publications, the incident generated a lot of bad

feeling at the time.

[6] if one excepts 1914 when the Eisteddfod

itself was cancelled due to the outbreak of World War I. The 1940 Eisteddfod

did not take place as planned in Mountain Ash, Rhondda Valley, due to World War

II, but an �Eisteddfod of the air� was held over the radio. The crown and chair

competitions took place; a chair was awarded but the crown was withheld.

[7] The 1940 Eisteddfod, which was to be held in Mountain Ash in the

Rhondda Valley, took place over the radio.

[8] 20/3/00

[9] This happens just before the crowning ceremony.

[10] Mind you, this phrase doesn�t have quite

the same ring to it when you say �the Welsh nationalist party leading the

visually challenged� ! The Welsh version is more alliterative "Y Blaid yn

blaenori y dall"

[11] �diadell yn bwysicach na diwylliant a

buches yn bwysichach na buchedd�

[12] Accounts available for last year�s Eisteddfod, which cost a similar amount to this year�s, show that over 90% of revenue for the festival was raised from a limited number of sources:

(i) tickets and admission £487,000, (ii) revenue from stalls/stands £352,000, (iii)broadcasting rights £300,000,

(iv) contributions from local authorities £316,000, (v) local fund £272,000, and (vi) sponsorship £359,000. In addition to income relating to individidual annual Eisteddfodau, the festival benefits from a general annual grant from the

Welsh Language Board of just under £300,000.

[13] Since 1880 the Eisteddfod has been held

outside Wales on six occasions: London (1887, 1909); Liverpool (1884, 1900,

1929); and Birkenhead (1917 - when Hedd Wyn was awarded the Chair

posthumously).

Traveling show

The festival location alternates between

north and south Wales every second year. This not only spreads the benefits

around the country but ensures the maximum involvement of the widest population

over time in the organisation of the festival and in its activities.

Preparations start two years in advance when the location is decided and a

large slice of the local population is mobilised in a vast voluntary effort.

With a full time staff of around 18, the festival relies on at least a thousand

volunteers both at national (Wales) and local level. The enthusiasm of the

voluntary workers, who range right through the religious, sporting, political,

age and gender spectrum, has to be experienced to be fully appreciated. This is

the International Year of Volunteers and the Eisteddfod has included the

festival in the Year�s 2001 celebrations.Denbigh 2001

Denbigh, the site of this year�s Eisteddfod, is in

Northeast Wales, near Rhyl, St. Asaph and Ruthin. While the modern (post 1880)

Eisteddfod has only visited Denbigh twice, in 1882 and 1939, it had been many

times in the region in the intervening years. There is a special meaning,

however, to having it in your own town. This year there was great excitement in

the town itself and in the surrounding areas at the prospect of being the epicentre

of Welsh culture for this one week of the year.

Denbigh, the site of this year�s Eisteddfod, is in

Northeast Wales, near Rhyl, St. Asaph and Ruthin. While the modern (post 1880)

Eisteddfod has only visited Denbigh twice, in 1882 and 1939, it had been many

times in the region in the intervening years. There is a special meaning,

however, to having it in your own town. This year there was great excitement in

the town itself and in the surrounding areas at the prospect of being the epicentre

of Welsh culture for this one week of the year.The Gorsedd circle

The Gorsedd circle[3],

consisting of a grouping of large standing stones and an �altar stone� arranged

in a pattern denoting the rays of the sun and the �ineffable name� of the Lord,

is specially constructed on the outskirts of each town for the Eisteddfod�s

first visit. It is used for some of the colourful druidic ceremonies, and

usually remains after the departure of the Eisteddfod, to be used again,

hopefully, on the return of the festival to the town in later years. Despite

the Eisteddfod having previously visited Denbigh, a new circle had to be

constructed for this year's festival. The old circle from 1939 had been built

over by the local Catholic church - reminiscent of the Church�s appropriation,

over the centuries, of pagan festivals into the liturgical calendar.

The Gorsedd circle[3],

consisting of a grouping of large standing stones and an �altar stone� arranged

in a pattern denoting the rays of the sun and the �ineffable name� of the Lord,

is specially constructed on the outskirts of each town for the Eisteddfod�s

first visit. It is used for some of the colourful druidic ceremonies, and

usually remains after the departure of the Eisteddfod, to be used again,

hopefully, on the return of the festival to the town in later years. Despite

the Eisteddfod having previously visited Denbigh, a new circle had to be

constructed for this year's festival. The old circle from 1939 had been built

over by the local Catholic church - reminiscent of the Church�s appropriation,

over the centuries, of pagan festivals into the liturgical calendar. Site

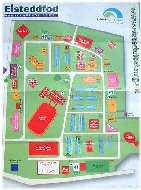

The Eisteddfod field proper (y maes) was a 35 acre

field, but the supporting space, car parks, caravan and camping sites, added

another 100 acres. The whole site was, conveniently, as flat as a pancake, and,

on this account, is known as the pacific field. Some youth activities, such as

gigs, were held on an adjacent field (maes B), in the town and the adjacent

towns of Rhyl and Ruthin. Prequalifying

tests for the competitions were held in halls on the maes, in local chapels and

the local high school.

The Eisteddfod field proper (y maes) was a 35 acre

field, but the supporting space, car parks, caravan and camping sites, added

another 100 acres. The whole site was, conveniently, as flat as a pancake, and,

on this account, is known as the pacific field. Some youth activities, such as

gigs, were held on an adjacent field (maes B), in the town and the adjacent

towns of Rhyl and Ruthin. Prequalifying

tests for the competitions were held in halls on the maes, in local chapels and

the local high school.Local involvement

Foot and Mouth

One of the big imponderables in the lead

up to this year�s Eisteddfod was the foot and mouth outbreak in the UK. While

the immediate area around Denbigh was not affected, the disease was rampant in

many of the areas from which both attendees and competitors would come to the

festival. In April, as the deadline approached a final decision, the organisers

were in a dilemma. They did not want to be the cause of bringing the disease

into the area and possibly spreading it to other areas in Wales. Nor did they

have any way of knowing whether the area might be subject to an outbreak in the

run up to the Eisteddfod. In the event the Welsh National Assembly came to the

rescue with a grant of £150,000 to underwrite contracts which had to be entered

into in April, but which would constitute losses if the festival were to be

cancelled. This allowed the organisers to postpone a final decision until the

beginning of May, when it was decided to go ahead. However, those living in

areas affected by foot and mouth were asked to seriously consider not

travelling to this year�s festival.

One of the big imponderables in the lead

up to this year�s Eisteddfod was the foot and mouth outbreak in the UK. While

the immediate area around Denbigh was not affected, the disease was rampant in

many of the areas from which both attendees and competitors would come to the

festival. In April, as the deadline approached a final decision, the organisers

were in a dilemma. They did not want to be the cause of bringing the disease

into the area and possibly spreading it to other areas in Wales. Nor did they

have any way of knowing whether the area might be subject to an outbreak in the

run up to the Eisteddfod. In the event the Welsh National Assembly came to the

rescue with a grant of £150,000 to underwrite contracts which had to be entered

into in April, but which would constitute losses if the festival were to be

cancelled. This allowed the organisers to postpone a final decision until the

beginning of May, when it was decided to go ahead. However, those living in

areas affected by foot and mouth were asked to seriously consider not

travelling to this year�s festival. Competitions

There are some 200 separate competitions

including serious poetry and prose, music, recitation, song and dance, arts and

crafts and technology based activities. There are also competitions in a

lighter vein such as writing scripts for stand-up comedians, or a series of correspondence

in email, limericks and even an amusing song about a soap opera. A recent

innovation was a competition for building a web site promoting the stand for

Welsh learners at the Eisteddfod or illustrating an aspect of Welsh life. This

was quite daring as the Eisteddfod itself only set up an official website last

year.

There are some 200 separate competitions

including serious poetry and prose, music, recitation, song and dance, arts and

crafts and technology based activities. There are also competitions in a

lighter vein such as writing scripts for stand-up comedians, or a series of correspondence

in email, limericks and even an amusing song about a soap opera. A recent

innovation was a competition for building a web site promoting the stand for

Welsh learners at the Eisteddfod or illustrating an aspect of Welsh life. This

was quite daring as the Eisteddfod itself only set up an official website last

year. However broad the range of competitions, interest

centres on a limited number of high profile categories. At the apex are the

poetry competitions for the crown and chair, followed by the contest for the

Prose medal. A high spot towards the end of the week is the male voice choir

competition for choirs of over 60 voices.

However broad the range of competitions, interest

centres on a limited number of high profile categories. At the apex are the

poetry competitions for the crown and chair, followed by the contest for the

Prose medal. A high spot towards the end of the week is the male voice choir

competition for choirs of over 60 voices.High points

My first Eisteddfod in Flint in 1969 was

seriously historical as this was the year of the Investiture of Prince Charles

as Prince of Wales. Everything that happened in Wales that year was qualified

by the word �Investiture�. This investiture Eisteddfod provoked serious

protests by the nascent Welsh Language Society and even the somewhat sparsely

populated, �Free Wales Army� of the day.

My first Eisteddfod in Flint in 1969 was

seriously historical as this was the year of the Investiture of Prince Charles

as Prince of Wales. Everything that happened in Wales that year was qualified

by the word �Investiture�. This investiture Eisteddfod provoked serious

protests by the nascent Welsh Language Society and even the somewhat sparsely

populated, �Free Wales Army� of the day. It was to happen soon again in 1976, when

Alan once more pulled off the double, but only because the winner of the chair

that year, Dic Jones, was disqualified over a technical conflict of interest.

As a member of one of the local Eisteddfod committees, Dic did not qualify to

enter the competition, but, as entries are adjudicated under pen names, this

was not picked up until the last minute.[5]

It was to happen soon again in 1976, when

Alan once more pulled off the double, but only because the winner of the chair

that year, Dic Jones, was disqualified over a technical conflict of interest.

As a member of one of the local Eisteddfod committees, Dic did not qualify to

enter the competition, but, as entries are adjudicated under pen names, this

was not picked up until the last minute.[5]

The literary competitions

There is intense interest throughout

Welsh-speaking Wales in the results of the main literary, and particularly the

poetry, competitions every year. Queues form at retail outlets on the field for

the published volume of adjudications and winning entries. This volume becomes

a sort of literary bible during the following year and it is minutely

scrutinised and hotly debated across the nation

There is intense interest throughout

Welsh-speaking Wales in the results of the main literary, and particularly the

poetry, competitions every year. Queues form at retail outlets on the field for

the published volume of adjudications and winning entries. This volume becomes

a sort of literary bible during the following year and it is minutely

scrutinised and hotly debated across the nationThis year�s results

The competition for the bardic crown,

for a series of at least ten poems in free verse and not more than 200 lines,

had been set on the theme �walls�. The winning entry dealt with how people

build psychological and social defences in their lives against the possibility

of hurt and end up isolating themselves from the rest of the human race, depriving

themselves of the sustenance needed for a full and balanced life.

The poem

follows a life sequence from the child building the walls of his lego castle to

higher walls leading to his self-imposed isolation. In later life this erupts

into violence towards his contemporaries, verbal violence against women in

general and physical abuse of his wife. It is a powerful work on a very

contemporary theme. We are left with the haunting image of the wife begging for

release while the husband hides his face in the newspaper . Meanwhile in public

she smiles wanly in an attempt to hide her bruises.

The competition for the bardic crown,

for a series of at least ten poems in free verse and not more than 200 lines,

had been set on the theme �walls�. The winning entry dealt with how people

build psychological and social defences in their lives against the possibility

of hurt and end up isolating themselves from the rest of the human race, depriving

themselves of the sustenance needed for a full and balanced life.

The poem

follows a life sequence from the child building the walls of his lego castle to

higher walls leading to his self-imposed isolation. In later life this erupts

into violence towards his contemporaries, verbal violence against women in

general and physical abuse of his wife. It is a powerful work on a very

contemporary theme. We are left with the haunting image of the wife begging for

release while the husband hides his face in the newspaper . Meanwhile in public

she smiles wanly in an attempt to hide her bruises.The chair

The competition for the bardic chair,

which involves a poem of not more than 200 lines in very strict traditional

metre (cynghanedd), had as its theme �renaissance� or �rebirth�.

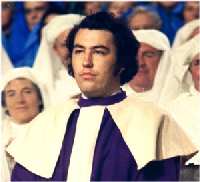

There are two magic moments at the culmination of

the poetry and prose competitions, more so the poetry than the prose and most

particularly the chair. The competitors have entered under pen-names. The Gorsedd

are assembled on stage, their bardic finery a sea of gold, white, blue and

green shimmering under the floodlights. They face out to a packed and eager

audience of 4,000 people. The air is electric as the adjudicator delivers the adjudication. The audience hang on

every word - has he found someone worthy of the prize? Will there be a chair?

There is a palpable sigh of relief as the pen name of the winner is revealed.

This is the first magic moment. The Archdruid proclaims the name from the stage

asking that person, and no other, to stand. The spotlight searches over the

hushed and darkened audience. Yes, someone has risen to their feet. The

spotlight finds them, a lighted winner in a vast sea of darkness. A collective

gasp which slowly turns to applause. Ever rising waves of cheering and clapping

roll around the pavilion. Everyone is on their feet.

There are two magic moments at the culmination of

the poetry and prose competitions, more so the poetry than the prose and most

particularly the chair. The competitors have entered under pen-names. The Gorsedd

are assembled on stage, their bardic finery a sea of gold, white, blue and

green shimmering under the floodlights. They face out to a packed and eager

audience of 4,000 people. The air is electric as the adjudicator delivers the adjudication. The audience hang on

every word - has he found someone worthy of the prize? Will there be a chair?

There is a palpable sigh of relief as the pen name of the winner is revealed.

This is the first magic moment. The Archdruid proclaims the name from the stage

asking that person, and no other, to stand. The spotlight searches over the

hushed and darkened audience. Yes, someone has risen to their feet. The

spotlight finds them, a lighted winner in a vast sea of darkness. A collective

gasp which slowly turns to applause. Ever rising waves of cheering and clapping

roll around the pavilion. Everyone is on their feet.  This was the defining moment of

this year�s Eisteddfod. For the first time in the history of the Eisteddfod,

the chair was won by a woman. Women had won the crown and the prose medal in

the past, though rarely. But the supreme honour had never been achieved by a

woman before. And now it had finally happened in Denbigh, where nobody had ever

won a chair, and, fittingly, where, at the 1882 Eisteddfod, women had first

been admitted to the Gorsedd.

This was the defining moment of

this year�s Eisteddfod. For the first time in the history of the Eisteddfod,

the chair was won by a woman. Women had won the crown and the prose medal in

the past, though rarely. But the supreme honour had never been achieved by a

woman before. And now it had finally happened in Denbigh, where nobody had ever

won a chair, and, fittingly, where, at the 1882 Eisteddfod, women had first

been admitted to the Gorsedd. A further piece of history was made when the

Archdruid kissed the Chair Bard onstage, a not so surprising first when one

considers that these two offices have been male preserves since time

immemorial. The Archdruid, whose term ends this year, also had the satisfaction

that there had been no chairs or crowns withheld on this three year watch.

A further piece of history was made when the

Archdruid kissed the Chair Bard onstage, a not so surprising first when one

considers that these two offices have been male preserves since time

immemorial. The Archdruid, whose term ends this year, also had the satisfaction

that there had been no chairs or crowns withheld on this three year watch. The winner was Mererid Hopwood. Her academic

training is in languages and she was recently Head of the Arts Council West and

mid Wales Office before venturing on the path of self-employment. She has been

studying cynghanedd for the last six years. She handled her press conference very adroitly, dealing very firmly with

the journalists.

The winner was Mererid Hopwood. Her academic

training is in languages and she was recently Head of the Arts Council West and

mid Wales Office before venturing on the path of self-employment. She has been

studying cynghanedd for the last six years. She handled her press conference very adroitly, dealing very firmly with

the journalists. On a lighter note, the Emer Feddyg Scholarship

was also won by a woman. The prize is for 3,000 words of prose in one of a

variety of forms. This year�s winner produced an outline for a novel, which, if

it saw the light of day �would be a shock for her mother and any other deacon�.

The name of the novel is �Hogan Horni� (horny girl), and we are promised

revelations about those who attend festivals, should the novel itself ever be

written and published.

On a lighter note, the Emer Feddyg Scholarship

was also won by a woman. The prize is for 3,000 words of prose in one of a

variety of forms. This year�s winner produced an outline for a novel, which, if

it saw the light of day �would be a shock for her mother and any other deacon�.

The name of the novel is �Hogan Horni� (horny girl), and we are promised

revelations about those who attend festivals, should the novel itself ever be

written and published.Ceremonial pageantry

TheGorsedd does not dispense magic, it

is a pageant, not a coven.

It was started in 1792 (AD!) by the �not altogether

honest� Iolo Morgannwg who intended it to replace the local/regional

Eisteddfodau of the day. He soon gave up that idea and decided to make the

Gorsedd part of the evolving National Eisteddfod. The first attempt at a

national Eisteddfod was made in 1858 in Llangollen but it was run by chancers

and turned into a den of thieves. Nevertheless it did lead to a further

Eisteddfod in Denbigh in 1860 at which it was decided to hold a single great

Eisteddfod for the whole nation once a year in North and South Wales

alternately and an Eisteddfod Council was set up to manage it. This did not

succeed and a new body was set up in 1880 to control the Eisteddfod. This point

is taken as the beginning of the �modern� Eisteddfod and with the exception of

1914 there has been an Eisteddfod every year since then[7].

It was started in 1792 (AD!) by the �not altogether

honest� Iolo Morgannwg who intended it to replace the local/regional

Eisteddfodau of the day. He soon gave up that idea and decided to make the

Gorsedd part of the evolving National Eisteddfod. The first attempt at a

national Eisteddfod was made in 1858 in Llangollen but it was run by chancers

and turned into a den of thieves. Nevertheless it did lead to a further

Eisteddfod in Denbigh in 1860 at which it was decided to hold a single great

Eisteddfod for the whole nation once a year in North and South Wales

alternately and an Eisteddfod Council was set up to manage it. This did not

succeed and a new body was set up in 1880 to control the Eisteddfod. This point

is taken as the beginning of the �modern� Eisteddfod and with the exception of

1914 there has been an Eisteddfod every year since then[7]. Today�s Gorsedd is the icing on the Eisteddfod cake,

providing pageantry and a sense of occasion to the national festival. In

inviting new members into its ranks it also serves as a kind of Welsh Wales

honours list, a function also carried out, in part, by the universities in

Wales when they award honorary degrees to deserving recipients.

Today�s Gorsedd is the icing on the Eisteddfod cake,

providing pageantry and a sense of occasion to the national festival. In

inviting new members into its ranks it also serves as a kind of Welsh Wales

honours list, a function also carried out, in part, by the universities in

Wales when they award honorary degrees to deserving recipients. The basic ceremonies are repeated on each occasion.

They are very colourful and packed with symbolism.

The basic ceremonies are repeated on each occasion.

They are very colourful and packed with symbolism. At each ceremony the massive Gorsedd sword is

partially unsheathed as the Archdruid declaims �Is there peace�? The audience

roar back �Peace�! The sword is fully returned to the sheath and the ceremonies

continue.

At each ceremony the massive Gorsedd sword is

partially unsheathed as the Archdruid declaims �Is there peace�? The audience

roar back �Peace�! The sword is fully returned to the sheath and the ceremonies

continue.The Archdruid

The office of Archdruid, or rather the method of

election of the Archdruid, has become controversial of late. Traditionally,

candidates had to come from among the winners of the crown or chair. Of the 24

Archdruids elected since 1900, 14 were national Eisteddfod chair bards (and

some had one or more crowns to boot). Of the 10 remaining, 9 had were crown

bards (with at least one crown) and the position of the 10th is not clear from

the literature to hand. In recent times, however, following a long campaign,

winners of the prose medal were considered suitable candidates.

The office of Archdruid, or rather the method of

election of the Archdruid, has become controversial of late. Traditionally,

candidates had to come from among the winners of the crown or chair. Of the 24

Archdruids elected since 1900, 14 were national Eisteddfod chair bards (and

some had one or more crowns to boot). Of the 10 remaining, 9 had were crown

bards (with at least one crown) and the position of the 10th is not clear from

the literature to hand. In recent times, however, following a long campaign,

winners of the prose medal were considered suitable candidates. The first product of the new system,

announced at the Gorsedd�s annual meeting in the Societies� tent on the field,

was Robyn Lewis. Currently the Board�s legal officer and a winner of the Prose

Medal, he had strenuously campaigned over the years to reform the system, and

in particular to raise the status of prose (and its medalists) to equal that of

poetry. It was a significant victory and one which could, in time, change the

character of the Gorsedd. He takes over as Archdruid next year and an

immediately perceptible change may be the dropping of the benign paternalistic

wit of former Archdruids in favour of a more serious and dogmatic presentation

of the office.

The first product of the new system,

announced at the Gorsedd�s annual meeting in the Societies� tent on the field,

was Robyn Lewis. Currently the Board�s legal officer and a winner of the Prose

Medal, he had strenuously campaigned over the years to reform the system, and

in particular to raise the status of prose (and its medalists) to equal that of

poetry. It was a significant victory and one which could, in time, change the

character of the Gorsedd. He takes over as Archdruid next year and an

immediately perceptible change may be the dropping of the benign paternalistic

wit of former Archdruids in favour of a more serious and dogmatic presentation

of the office.  While he himself declined to be drawn on how he

would handle the office, and gave the impression of being very cautious, there

is some ground for expecting the odd impulsive outburst at future Gorsedd

sessions. That is not to say that they will go unchallenged.

While he himself declined to be drawn on how he

would handle the office, and gave the impression of being very cautious, there

is some ground for expecting the odd impulsive outburst at future Gorsedd

sessions. That is not to say that they will go unchallenged.Celtic fraternal delegates

One of the functions of the Gorsedd during

Eisteddfod week is to formally welcome the delegates from the national festival

(or Gorsedd, if they have one) of each of the Celtic countries. There are two

delegates each from Ireland (Oireachtas na Gaeilge), Scotland (Mod), Isle of

Man (Cruinnacht) and the Gorseddau of Brittany and Cornwall.

One of the functions of the Gorsedd during

Eisteddfod week is to formally welcome the delegates from the national festival

(or Gorsedd, if they have one) of each of the Celtic countries. There are two

delegates each from Ireland (Oireachtas na Gaeilge), Scotland (Mod), Isle of

Man (Cruinnacht) and the Gorseddau of Brittany and Cornwall. The Gorsedd also mourns the passing of

its members who died during the past year, recites their names, and calls on

God�s merciful protection for their

mourning families and surviving partners (where applicable!).

The Gorsedd also mourns the passing of

its members who died during the past year, recites their names, and calls on

God�s merciful protection for their

mourning families and surviving partners (where applicable!). The Celtic countries reciprocate by

inviting representatives from the Gorsedd to attend their festivals. In his

report to the Gorsedd on his visit to the Oireachtas last year, the

Archdruid commented on the enthusiasm of the welcome extended to himself, the

Deputy Archdruid, and their wives, to the festivities in Clontarf Castle and

the competitions in CUS He thanked various people, including Bl�thnaid,

�without whose presence, and that of her husband, no Celtic festival is

complete�.

The Celtic countries reciprocate by

inviting representatives from the Gorsedd to attend their festivals. In his

report to the Gorsedd on his visit to the Oireachtas last year, the

Archdruid commented on the enthusiasm of the welcome extended to himself, the

Deputy Archdruid, and their wives, to the festivities in Clontarf Castle and

the competitions in CUS He thanked various people, including Bl�thnaid,

�without whose presence, and that of her husband, no Celtic festival is

complete�.

Formal cultural activities

Stand and deliver

The pavilion is surrounded by up to 300

stalls, stands, halls and facilities of all sorts, including a broadcasting

campus. Some activities merit solid structures: the Eisteddfod Arts and Crafts

exhibition, the Welsh Arts Council, the learners, literature, and dance

pavilions, field theatre, Denbishire County Council and Welsh Development

Authority (to name most of them).

Daily tickets to the field cost £8

(sterling !). This included admission to the daytime events in the pavilion -

consisting of competition finals, adjudications and the main Gorsedd-sponsored

literary investitures. Given the importance and intensity of the field

activities during Eisteddfod week, this was good value, particularly for

Welsh-speaking enthusiasts.

Daily tickets to the field cost £8

(sterling !). This included admission to the daytime events in the pavilion -

consisting of competition finals, adjudications and the main Gorsedd-sponsored

literary investitures. Given the importance and intensity of the field

activities during Eisteddfod week, this was good value, particularly for

Welsh-speaking enthusiasts.  The broadcasting companies were very much to the fore

in this. BBC-Cymru (Welsh language radio programmes) ran live gigs on the field

all through the day and some of these were broadcast live on the Welsh network.

They also provided a range of computer zap-em-up games for the emotionally

challenged child. S4C, the Welsh language amalgam TV network, provided an

opportunity for children to meet characters from their favourite soaps and

access various facilities on their website.

The broadcasting companies were very much to the fore

in this. BBC-Cymru (Welsh language radio programmes) ran live gigs on the field

all through the day and some of these were broadcast live on the Welsh network.

They also provided a range of computer zap-em-up games for the emotionally

challenged child. S4C, the Welsh language amalgam TV network, provided an

opportunity for children to meet characters from their favourite soaps and

access various facilities on their website.Penffordd

But the daddy of them all, when it came to live

entertainment on the field, was a newly-formed company called Penffordd. It

provided all day, open air, entertainment for adults and children alike and it

was a rare hour of the day that overspilling family audiences were not blocking

the thoroughfare. They were worth the price of admission on their own.

But the daddy of them all, when it came to live

entertainment on the field, was a newly-formed company called Penffordd. It

provided all day, open air, entertainment for adults and children alike and it

was a rare hour of the day that overspilling family audiences were not blocking

the thoroughfare. They were worth the price of admission on their own. Penffordd ran one of the most innovative

and entertaining informal events of the festival when it organised a �karaoke�

competition between the National Assembly members of themain political parties in Wales, to be

adjudicated by a live audience on the spot.

Penffordd ran one of the most innovative

and entertaining informal events of the festival when it organised a �karaoke�

competition between the National Assembly members of themain political parties in Wales, to be

adjudicated by a live audience on the spot. In the event the contest was a hoot and each of the

National Assembly members entered fully into the spirit of the event. The Tory

member did turn up, sporting a large gold pound sterling brooch on his lapel,

and he did recite a poem and it was karaoke - the Liberace style accompaniment

on the keyboard made sure of this. The Lib-Dems fancied their chances with a

lady who had clearly sung before and the Labour Party relied on the proletarian

vote. But the winner was the clever lady from Plaid Cymru (Y Blaid) who had no

hesitation in admitting, after the event, that she had packed the audience. The

days of the Blaid leading the Blind are not yet a thing of the past.[10]

In the event the contest was a hoot and each of the

National Assembly members entered fully into the spirit of the event. The Tory

member did turn up, sporting a large gold pound sterling brooch on his lapel,

and he did recite a poem and it was karaoke - the Liberace style accompaniment

on the keyboard made sure of this. The Lib-Dems fancied their chances with a

lady who had clearly sung before and the Labour Party relied on the proletarian

vote. But the winner was the clever lady from Plaid Cymru (Y Blaid) who had no

hesitation in admitting, after the event, that she had packed the audience. The

days of the Blaid leading the Blind are not yet a thing of the past.[10]Visual Arts and Crafts exhibition

The Eisteddfod�s own Visual Arts and

Crafts exhibition, containing a selection of work chosen from over 2,000

individual works submitted by over 400 artists, is rightly described by the

selectors as �a strange, many-headed beast�. The Chairperson of the Arts and

Crafts Committee expressed a wish, and a hope, that the exhibition would be a

�topic of discussion on the Eisteddfod field, nationally throughout Wales and

further afield on the international level�. It was certainly a hot topic on the

field.

The Eisteddfod�s own Visual Arts and