In the blood? In the blood?

My father was a photographer, or so I gather, but I never saw a single photo of his.

There was supposed to be a stash of photos and negatives in Ballyhaunis but they have never been found. I'm sure I would have found them fascinating. Maybe that's where I got my interest or maybe not. We never discussed photography and when I had a problem with what I thought was focus he didn't identify the real problem which was camera shake. These two problems are as alike as chalk and cheese to a photographer and are clearly distinguishable in the defective photos

The Machine.

The Machine.

Anyway, I started on a 116 bellows camera, which was primitive, even by then. It was, however, a beautifully crafted instrument and the larger negative size gave better definition than was generally available except to the Rolleiflex and Hasselblad operators, most of whom were professional and well capitalised. The illustration gives a fairly close idea of what it looked like - I couldn't find an illustration of the actual model I had. Anyway, I started on a 116 bellows camera, which was primitive, even by then. It was, however, a beautifully crafted instrument and the larger negative size gave better definition than was generally available except to the Rolleiflex and Hasselblad operators, most of whom were professional and well capitalised. The illustration gives a fairly close idea of what it looked like - I couldn't find an illustration of the actual model I had.

I eventually "graduated" to 35mm and slowly worked my way through a number of cameras.

The first of these was an East German single lens reflex (SLR) with a ground glass screen. Great for scenery but impossible to follow movement through the lens as everything went backwards. To capture movement you had to use the pop up viewfinder and forgo SLR mode.

I didn't grow out of this camera, however, I lost it on the main pier in St. Helier, Jersey, in 1961. I could never make up my mind which loss I regretted most: the camera itself or the full role of slides I had just taken of the beautiful city of St. Malo with its castellated ramparts.

I then got a Beirette, which I think cost �7, and later graduated to the Yashica Minister II which saw me through a few more years. This had a much better lens than the Beirette but was still not an SLR and you could not change the focal length of the lens.

I finally rose to a Pentax in the mid seventies when Mam went to Japan and Father Brendan and Father Horgan shepherded her through the market to find my prize. I was slightly disappointed to find that the interchangeable lens fitting was a screw rather than a bayonet, the latter being much quicker to change in the heat of action. Pentax had apparently decided that the screw fitting was more accurate. Fine. Why then did they subsequently change to a bayonet fitting, particularly for their digital range of SLRs. If I ever graduate to one of these my existing telephoto and wide angle lenses will be no use to me. I finally rose to a Pentax in the mid seventies when Mam went to Japan and Father Brendan and Father Horgan shepherded her through the market to find my prize. I was slightly disappointed to find that the interchangeable lens fitting was a screw rather than a bayonet, the latter being much quicker to change in the heat of action. Pentax had apparently decided that the screw fitting was more accurate. Fine. Why then did they subsequently change to a bayonet fitting, particularly for their digital range of SLRs. If I ever graduate to one of these my existing telephoto and wide angle lenses will be no use to me.

In the current digital environment, and given that I am populating my website with current as well as past photos, it became clear that I needed to graduate to something decent in the digital camera line. I didn't quite feel justified in lashing out on an digital SLR at this stage but I wanted a fairly versatile instrument with a good range of manual controls. I also wanted good resolution, not for the web, but in the event of my following up on my aborted career in journalism. I finally settled on the Olympus mju 800. It has 8 megapixels with a very bright LCD viewfinder; definition is good, though it does not save as raw or bmp; it has a wide range of manual overrides; "film" sensitivity varies from 64 to 1600 ISO; it has a 3x optical zoom (roughly = 35mm-100mm) and can take a remote for tripod work. It can also take up to 1 hour video with good sound (.MOV) and the whole thing seems very sturdy with very well thought out controls. There is a review here.

In the current digital environment, and given that I am populating my website with current as well as past photos, it became clear that I needed to graduate to something decent in the digital camera line. I didn't quite feel justified in lashing out on an digital SLR at this stage but I wanted a fairly versatile instrument with a good range of manual controls. I also wanted good resolution, not for the web, but in the event of my following up on my aborted career in journalism. I finally settled on the Olympus mju 800. It has 8 megapixels with a very bright LCD viewfinder; definition is good, though it does not save as raw or bmp; it has a wide range of manual overrides; "film" sensitivity varies from 64 to 1600 ISO; it has a 3x optical zoom (roughly = 35mm-100mm) and can take a remote for tripod work. It can also take up to 1 hour video with good sound (.MOV) and the whole thing seems very sturdy with very well thought out controls. There is a review here.

Although I had the Olympus as my primary (and only) camera for 8 years and found it very satisfactory for what it was, I always missed the controls I had with the Pentax. Principal among those was the ability to focus manually, but also to easily change the speed and aperture and to save the image in greater resolution than JPG. Although I had the Olympus as my primary (and only) camera for 8 years and found it very satisfactory for what it was, I always missed the controls I had with the Pentax. Principal among those was the ability to focus manually, but also to easily change the speed and aperture and to save the image in greater resolution than JPG.

I was fortunate this Christmas in two respects. I was in a position to get a substantial present and in checking that out a friend offered me the gift of a Nikon D200 SLR body and I used the Christmas present to get a high quality zoom lens (18-100mm), flash and some other peripherals.

So I am now the proud possessor of what you see here (hover the cursor for a larger image). The picture shows a top view and a maze of controls and information, but every side of the camera is festooned with various controls and I suspect it will take me at least a year to get the hang of all of them. It's like going from a Cessna to an Airbus. I have my manual focus and photos can be saved in the amazing, if space consuming, RAW format, described by my friend as "the dark side". Magic.

A quick word on RAW. It has been described as a digital negative, insofar as it mirrors, to some extent, the wider dynamic range in negative film compared with the narrower range in the resulting hardcopy print. Effictively it stores a huge amount of information from the camera sensor and thereby allows a much wider post manipulation of the image than would be possible in already compressed JPEG images. For example, the extent to which you can correct the exposure without losing the dynamic range of the digital photo is extraordinary. It is heavy on space, though, taking up some 15MB per shot. But it is well worth it.

I have now replaced the Olympus which had been getting a bit cumbersome to carry round and whose specs were now seriously overtaken. My choice was the Sony WX350 Compact Camera with 20x Optical Zoom. I got it for just under €200 in Conn's Camera's in Dublin and it is just magic. It's hardly any bigger than a packet of cigarettes so I can have it always with me. I have it now just over a year and am nowhere near exploring its full capability. For instance I could mount it on a tripod and control certain features from my phone including seeing the screen. I don't know what sort of software is in it but a handheld 20x zoom shot comes out pin sharp. Recommended.

I have now replaced the Olympus which had been getting a bit cumbersome to carry round and whose specs were now seriously overtaken. My choice was the Sony WX350 Compact Camera with 20x Optical Zoom. I got it for just under €200 in Conn's Camera's in Dublin and it is just magic. It's hardly any bigger than a packet of cigarettes so I can have it always with me. I have it now just over a year and am nowhere near exploring its full capability. For instance I could mount it on a tripod and control certain features from my phone including seeing the screen. I don't know what sort of software is in it but a handheld 20x zoom shot comes out pin sharp. Recommended.

The Peripherals.

The Peripherals.

It must be very difficult for a young person today who starts off with a digital camera to imagine the peripherals photographers had to cart around with them in the "old days". When I was beginning there were very few, if any, SLRs around and the ordinary cameras did not have built in rangefinders so you would need a separate one of these. At a later stage they came fitted into the camera.

You would also need a flash gun and loads of flashbulbs. Each bulb was only good for a single flash. You couldn't set the shutter faster than 1/30th of a second and the camera fired the flash just before the shutter opened as the bulb took a while to reach maximum brightness. Electronic flash, when it came, was different. It reached its peak within 1/1000th of a second so the shutter had to be fully open when the flash fired. This led to dual nipple cameras with parallel fittings for electronic and bulb flash.

Flash was always a nuisance to deal with. Apart from having to lug the stuff around, gauging the exposure could often be tricky. The advent of the automatic exposure electronic flash was a great boon. The flash unit incorporated a sensor which detected the reflection of the flash and immediately shut itself down. You set an aperture for a particular film speed and rough distance and the unit took care of the rest. Miraculous, or "mirabile visu" as we used to say in our Latin class in school.

Carry a Camera.

Carry a Camera.

There is nothing worse than missing a good photo. The frustration of seeing a good picture but not having your camera with you is something else. Nowadays, if you put your mind to it, you can bring your camera everywhere with you and nobody is the wiser. Small digital cameras with very acceptable definition are two a penny. But in times past you drew attention to yourself carrying your camera with you wherever you went so you had to be either very dedicated or just plain oblivious.

As a result of carrying my camera on most occasions I have a vast collection of negatives and slides built up over the years. I have never actually seen prints of some of the negatives. It was much cheaper to simply get the negatives developed and subsequently choose a few to have printed than it was to leave in the roll for developing and printing. In any event there were always shots which did not succeed and they would print and charge you for these too.

In the last few years I have been uploading a lot of these to this site. But endless strings of photos would be boring so I am using a plain photogallery , along with some slide shows on specific topics, and, finally, writing up my experiences as an excuse to slip in a few more photos. In the last few years I have been uploading a lot of these to this site. But endless strings of photos would be boring so I am using a plain photogallery , along with some slide shows on specific topics, and, finally, writing up my experiences as an excuse to slip in a few more photos.

But I digress. There were some particular occasions when I was glad I had my camera with me.

I was at the Arc de Triomphe, in Paris, in the mid sixties when a girl took her own life. I didn't see her fall, but arrived in time to take a shot before the police came. The shot here is the second one taken after the police arrived.

I also had my camera with me when I came across the students who had taken temporary custody of Nelson's head for a fashion shoot on Killiney beach. I also had my camera with me when I came across the students who had taken temporary custody of Nelson's head for a fashion shoot on Killiney beach.

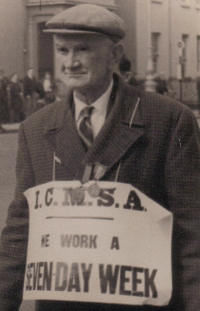

I had it with me when the ICMSA protested outside the D�il in Kildare Street in the late sixties and were taken away in Paddy Wagons.

The Darkroom

The Darkroom

The darkroom was the heart of the mystery with its red or green lighting. It was to here the photographer retired to turn his creations into something that could be shared with a wider public. Film was developed and prints or enlargements made, all fully under the photographer's own control. Those of us who didn't have darkrooms envied this control as we submitted our own films to the local chemist for dispatch to the nearest processing station. Frequently our attempts at artistic rendition were thwarted by automatic printing machines. The negatives over which we had control and which could simultaneously capture a very wide range of lighting conditions were squeezed into the narrower range of the photopaper.

I frequently opted to use slide [positive] film which involved only one process and where, in effect, you got the photo you thought you were taking. Slides had the added advantage that you could organise slide shows and pontificate to a captive audience in thrall to the huge pictures on the wall.

Even without a darkroom you could at least develop your own films. And more particularly so if they were black and white rather than colour which required a much more complicated procedure. The film could be removed from the camera, or in the case of 35mm from its casette, and transferred to a small plastic lightproof tank, all inside a lightproof black bag. The processing could then be done in daylight. Even without a darkroom you could at least develop your own films. And more particularly so if they were black and white rather than colour which required a much more complicated procedure. The film could be removed from the camera, or in the case of 35mm from its casette, and transferred to a small plastic lightproof tank, all inside a lightproof black bag. The processing could then be done in daylight.

If you could organise an approximation to a darkroom, you could then do your own printing or enlarging. With 35mm and the demise of the larger negative films, it had to be enlarging. I did a little of this in the attic in Ballybrack but it was very tedious. People who were really serious about it joined photographic clubs and availed of their darkroom facilities. I never quite got that far.

In today's digital age, the computer is your darkroom, and you can do it all in daylight. Retouching skills which it took traditional photographers years to acquire can now be learned in a day and applied by all and sundry. No doubt the real digital photo manipulators can do it better, but the amateur can make a very good shot at it and produce results which would have scarified a photographer in, say, the 1950s.

Look, No Camera!

Look, No Camera!

You could do some very interesting things in a darkroom. You could, for instance, have turned your enlarger, or any light source, into a photocopier, at a time when photocopiers cost the earth. You could do some very interesting things in a darkroom. You could, for instance, have turned your enlarger, or any light source, into a photocopier, at a time when photocopiers cost the earth.

Nothing could be easier.

- lay the image to be copied face up on a flat surface

- cover it with a piece of photographic paper, emulsion side down

- expose to light

- develop - this gives a negative image

- repeat the process to get a positive.

Primitive but effective.

The example above was done in the late sixties. The image is from a 1920s newspaper and if you hover your cursor over the negative image you can read the text.

A Fine Art.

A Fine Art.

Some of the afficianados of the "fine arts" will look down their noses at the photographer. After all, pushing a button doesn't, on the face of it, appear to equate with painting a Rembrandt.

Despite the skill or art involved in actually doing a painting, the painter's objective was often to produce an evocative representation of a real life object or scene. The photographer can do that today without needing the same painting skills. Despite the skill or art involved in actually doing a painting, the painter's objective was often to produce an evocative representation of a real life object or scene. The photographer can do that today without needing the same painting skills.

Does this make photography any the less of a "fine art"? Not in my book. If a definition of "fine art" revolves purely around technique then we've lost the plot. A good photographer can produce a work every bit as impressive and evocative as a classical painter. And this involves the essentials of any visual art: an eye for a good subject, both in terms of visualisation and relevance; a good sense of composition and colour/shading; the ability to capture this on a medium which allows others to share it.

Part, at least, of the exclusiveness claimed for the "fine arts" surely comes from snobbery, from a resistance to the democratisation of art through photography. We are now living in an age where some of the means of expression and diffusion, which were previously reserved to elites, are available to everyone. Not everyone may rise to the challenge and make the best use of them, but we now have to make a judgement call on the quality of the output rather than passively accepting works on the basis of the artist's label or brand.

This can seriously damage your comfort zone. Which is, after all, a consummation devoutly to be wished!

|

Photography

Photography