NLI&I

Me and the National Library of Ireland

Today, the National Library of Ireland (nli) has spread out beyond the confines of its original building to the premises of the old Kildare St. Club (where the stone monkeys play snooker on the window frame) and even as far as Temple Bar (the photo archive). It also has a significant online presence, so, depending on what you're after, you may not need to go anywhere near the place.

In my day, public access was confined (almost wholely) to the reading room, and what an imposing room that was, and still is.

It is just over forty years since I first called on the National Library of Ireland. My print of the photo below is dated 7 March 1973. That was when I first started chasing up the history of my own locality, Ballybrack/Killiney, in south County Dublin and I had occasion to call on the services of the Library. Quietly reposing within its hallowed walls were the Lawrence Photo Collection and the Hayes Catalogue of Irish Manuscript Sources. I fairly disturbed their quiet repose for a brief period of intensive inspection. In more recent times, in the mid Noughties, when I was following up my family origins, I again had occasion to call on the Library's services. This time it was the old Roman Catholic Parish Registers. And my most recent call, in 2012, has been to check out the Brewster Cartoon Collection, again as part of following up my family history.

These contacts have convinced me what a wonderful resource the National Library of Ireland is. Apart from the actual source material, the staff are enthusiastically cooperative and the Library itself is moving with the times, particularly in the digitisation of their resources. Digitisation not only makes these resources available to those who can't visit the premises, it also makes them digitally searchable, a real quantum leap for researchers.

Anyway, I'm just touching below, in more detail, on some of my experiences referred to above.

In my day, public access was confined (almost wholely) to the reading room, and what an imposing room that was, and still is.

It is just over forty years since I first called on the National Library of Ireland. My print of the photo below is dated 7 March 1973. That was when I first started chasing up the history of my own locality, Ballybrack/Killiney, in south County Dublin and I had occasion to call on the services of the Library. Quietly reposing within its hallowed walls were the Lawrence Photo Collection and the Hayes Catalogue of Irish Manuscript Sources. I fairly disturbed their quiet repose for a brief period of intensive inspection. In more recent times, in the mid Noughties, when I was following up my family origins, I again had occasion to call on the Library's services. This time it was the old Roman Catholic Parish Registers. And my most recent call, in 2012, has been to check out the Brewster Cartoon Collection, again as part of following up my family history.

These contacts have convinced me what a wonderful resource the National Library of Ireland is. Apart from the actual source material, the staff are enthusiastically cooperative and the Library itself is moving with the times, particularly in the digitisation of their resources. Digitisation not only makes these resources available to those who can't visit the premises, it also makes them digitally searchable, a real quantum leap for researchers.

Anyway, I'm just touching below, in more detail, on some of my experiences referred to above.

The Lawrence Photo Collection

At the very beginning of my local history research, I went straight to the Lawrence Photo Collection and checked out the catalogue for every picture identified with the area I was interested in - Killiney Bay, Ballybrack and the surrounding areas. This meant including Loughlinstown, Lehaunstown, Hacketsland, Shankill, Kilbogget, Rochestown etc. I then ordered the photos up to check them out and imagine my amazement when my first order appeared at my table. This consisted of a stack of the original glass plate negatives. Drop one of those and it's gone forever. Today, with modern technology, the plates have been scanned and you can either inspect microfilm miniatures as a basis for ordering prints or order from online images.

Having selected what I wanted, and could afford, I placed a final order and the prints were posted out to me some weeks later. I used these photos to explore the area as it was over the period roughly from [1880 to 1910]. Sometimes there would effectively be a time series of roughly the same shot which showed new houses, more trees, new railway station, railway diverted inland etc. They were fantastic graphic images of history in motion.

The resolution in these photos was exceptional, not surprising given the size of the glass plate negatives [dimensions - 10"x8" ?]. Inspection through a good quality magnifying glass revealed a wealth of further detail. By way of illustrating this I am giving the example below.

Having selected what I wanted, and could afford, I placed a final order and the prints were posted out to me some weeks later. I used these photos to explore the area as it was over the period roughly from [1880 to 1910]. Sometimes there would effectively be a time series of roughly the same shot which showed new houses, more trees, new railway station, railway diverted inland etc. They were fantastic graphic images of history in motion.

The resolution in these photos was exceptional, not surprising given the size of the glass plate negatives [dimensions - 10"x8" ?]. Inspection through a good quality magnifying glass revealed a wealth of further detail. By way of illustrating this I am giving the example below.

With thanks to the National Library of Ireland

There are some features in this photo which help date it. The combined Killiney/Ballybrack station makes is post 1882. The railway running along cliffs makes it pre 1914, when the railway was diverted inland due to cliff erosion along the original line. The possible absence of Seafield Road beyond the old Ballybrack Railway Station would put it before c.1900 as the extended road and big houses on that road (Inveruisk and Aughnacloy) show up on the 1900 OS 25" map. It is not clear if the photo shows the absence of those big houses, I still need to do a careful survey on the ground to establish that. But if it does show they were not there, then Thoms Directory would bring the photo even further back, as those houses show up in the 1884 edition which means they were there in 1883. In that case, the photo would have been taken in 1882 or early 1883, though the serial number would suggest a much later date.

Further close inspection of the photo brings out other historically significant features.

Further close inspection of the photo brings out other historically significant features.

The site of the limekiln at the railway road-bridge is clearly visible. This is the white cottages on the nearside of the castellated house. I only recently discovered the location of this limekiln and was assuming this was the location of the limekiln which gave its name to Battery No. 8 at the north end of Station Road. When I moved to Ballybrack in 1954 there was still the remains of a cottage there, but further cliff erosion has completely done away with that. Following a recent talk by Rob Goodbody, to the Ballybrack and Killiney Historical Society, on the history of the road system in the area, I think I may have to revise my view and locate the pre 1804 limekiln further north to the bottom of the Kilmore Avenue.

There are horse cabs at the station to drop and pick up the local gentry. The coming of the railway meant that a lot of important people could live in Killiney/Ballybrack and commute to work in town. In fact that rail journey was every bit as fast then as it is today.

There are horse cabs at the station to drop and pick up the local gentry. The coming of the railway meant that a lot of important people could live in Killiney/Ballybrack and commute to work in town. In fact that rail journey was every bit as fast then as it is today.

You can see Martello Tower No. 4 on Mahera point (1804) at the extreme left in the middle of the picture. This is long gone - dismantled when it became a risk with the erosion of the cliff. There were originally two Batteries here as well, one on either side of the Tower, both of which suffered the same fate.

At the bottom right of the picture, you can see the northern outer perimeter wall of Battery No.5 (1804), which cuts horizontally across the railway track (1854). This Battery and its adjoining land stretched along the cliff on the far side of the wall. This is now largely gone with the erosion/collapse of the cliff over time. In fact this Battery was abandoned as early as 1815 for this very reason.

You can see the full range of permanent military emplacements in Killiney Bay here.

At the bottom right of the picture, you can see the northern outer perimeter wall of Battery No.5 (1804), which cuts horizontally across the railway track (1854). This Battery and its adjoining land stretched along the cliff on the far side of the wall. This is now largely gone with the erosion/collapse of the cliff over time. In fact this Battery was abandoned as early as 1815 for this very reason.

You can see the full range of permanent military emplacements in Killiney Bay here.

The Hayes Catalogue of Irish Manuscript Sources

My next stop was the Hayes catalogue of Irish manuscript sources. This catalogued manuscripts of Irish interest which were not only in the National Library but also in certain other institutions, including the British Museum and the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

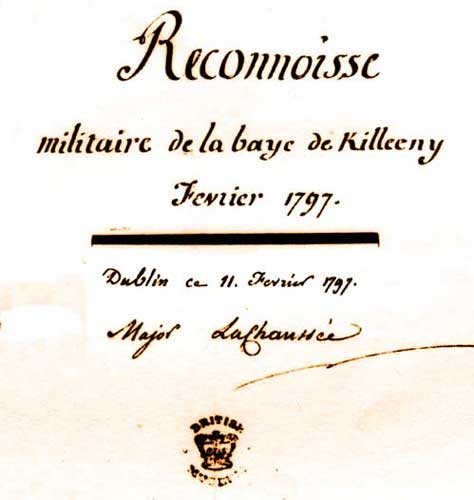

And here I struck gold. Under Killiney there was a card entry for a military reconnaisance of the Bay by a French major. I got a photocopy of the document from the British Museum and my excitement mounted as I read this very erudite analysis, in French, of the vulnerable spots in the Bay where the French might profitably land an invading force.

I was convinced I was reading the report of a French spy until I came to the Appendix where the major's orders were set out. These were in English and came from the commander of the British forces, Lord Carhampton. The major, presumably a refugee from the French Revolution, was actually working for the British and analysing the Bay's vulnerabilities from a defensive point of view. Despite my disappointment, this was an exciting find, and it changed my view of the Bay. It is no longer a piece of nice scenery, as it appears above, but a potential battlefield. I can almost see the French ships in the Bay.

The major's analysis laid the basis for the location of the Martello Towers and Batteries some seven years later. You can read up on my quest for La Chauss�e here.

The major's analysis laid the basis for the location of the Martello Towers and Batteries some seven years later. You can read up on my quest for La Chauss�e here.

The Parish Registers

The National Library also holds microfilm of most of the Roman Catholic Parish Registers for the period [1800 -1900 ?]. These are important sources for genealogists, or anyone trying to trace their family origins. This is particularly so for the period before 1864/6 when the keeping of civil records of births, deaths and marriages began.

I discovered records of the marriages of two sets of great-grandparents in the microfilm of the Pro Cathedral registers and they provided a lot of incidental information which helped me trace the families further back.

However, when I subsequently tried to check out the origins of a third set of great-grandparents I ran into a brick wall. I had identified and requested the appropriate roll of microfilm and the lady was standing in front of me with it in her hand. "This is what you wanted, but I can't give it to you" she said. "Why not?" I asked. "Because you need the Bishop's permission to view it". "How do I get that". "You have to ring the palace".

As it turned out, this particular bishop never gave his permission and the only alternative was to fork out €80 to the diocesan Heritage Centre, for a search that might, or might not be complete and accurate. As it happened, I got access to the digitised records by devious means, but was still left with a query over one individual. To establish whether or not they were part of my family I needed to examine the actual register. Fortunately by this time the National Library had bravely decided to ignore this particular bishop, so I finally got to see the records. And yes, it was worth it. One parent of this individual had been incorrectly identified in the transcription and thereby excluded from my digital family. I was now able to rectify this mistake, claim this relative as my own, and tidy up other pieces of the jigsaw.

However, when I subsequently tried to check out the origins of a third set of great-grandparents I ran into a brick wall. I had identified and requested the appropriate roll of microfilm and the lady was standing in front of me with it in her hand. "This is what you wanted, but I can't give it to you" she said. "Why not?" I asked. "Because you need the Bishop's permission to view it". "How do I get that". "You have to ring the palace".

As it turned out, this particular bishop never gave his permission and the only alternative was to fork out €80 to the diocesan Heritage Centre, for a search that might, or might not be complete and accurate. As it happened, I got access to the digitised records by devious means, but was still left with a query over one individual. To establish whether or not they were part of my family I needed to examine the actual register. Fortunately by this time the National Library had bravely decided to ignore this particular bishop, so I finally got to see the records. And yes, it was worth it. One parent of this individual had been incorrectly identified in the transcription and thereby excluded from my digital family. I was now able to rectify this mistake, claim this relative as my own, and tidy up other pieces of the jigsaw.

The Brewster Cartoons

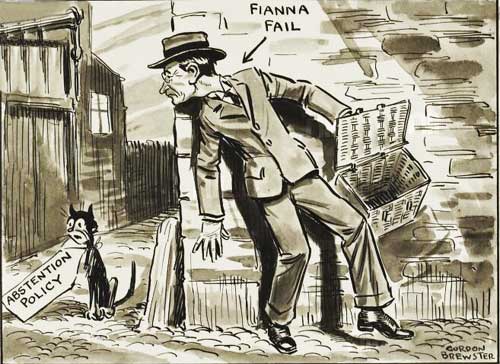

With thanks to the National Library of Ireland

The story of my connection to date with the National Library would not be complete without mention of the Brewster Cartoons. You can read about this in a guest posting on the library's own excellent blog.

As well as giving me some inkling of what goes on behind the scenes at NLI, my inspection of the cartoon collection and subsequent drafting of the guest post brought me into direct contact with Honora Faul and Carol Maddock and I'd like to take this opportunity to pay tribute to their enthusiasm, dedication and professionalism.

As well as giving me some inkling of what goes on behind the scenes at NLI, my inspection of the cartoon collection and subsequent drafting of the guest post brought me into direct contact with Honora Faul and Carol Maddock and I'd like to take this opportunity to pay tribute to their enthusiasm, dedication and professionalism.