Reflections on a Welsh Graveyard

|

Llanfairisgaer is a rural graveyard on the mainland side of the Menai Straits, in North Wales. One version of history has it that this is where the Romans launched their attack on Anglesea, which was then the last refuge of Celt and Druid alike. Alongside an old church, with some interesting stained glass windows, the graveyard consists three sections, the older two of which are on open access and the third modern section is under permanent lock and key. The remarks that follow refer, therefore, to the two older sections. By the standards of graveyards, Llanfiarisgaer is a place of serenity, of acceptance, of the solidity of community. More important where a person was born than what they have done. No bitterness, even in the striking down of the very young, the waste of death in war, or in the passing of the very old with all their accumulated wisdom and newly budding family branches. Here is a place of rest. The tragic circumstances of death yielding to the reality of eternity. |

|

And the slate everywhere. This local stone which had both claimed lives in its harvesting and commemorated those same lives in death. The local rock which sheltered during life and honoured after death.

|

|

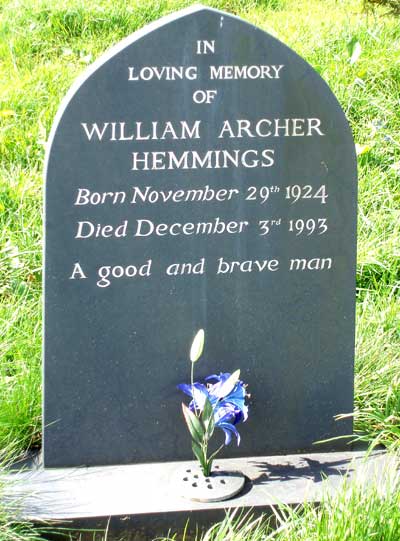

I have often thought that the extravagence of memorials is in inverse proportion to the worth of the person being commemorated. Perhaps that is not entirely, or always, fair. But you can't help feeling a sense of denial, of non-acceptance, of plain posthumous snobbery, in many of the grand monuments in some graveyards. Here, there is dignity in simplicity. |

|

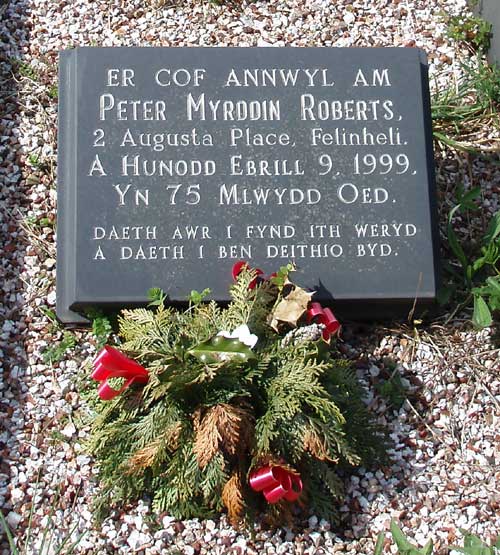

This area was known as Port Dinorwic but was eventually awarded what was considered a more Welshified name "Y Felinheli" the saltwater mill. This is still seen locally as a modern construction and seems to be borne out in the Welsh language inscriptions on the gravestones, most of which refer to Port Dinorwic, but with the only partly Welsh spelling. Having said that see the next one which is one of the few which refers to Y Felinheli. |

|

Some tombs make point about the prevailing orthography. Today July would be rendered Gorffennaf with the "f" sound rendered with an "ff" in Welsh. This tomb seems to be nodding in the direction of English orthography by rendering it with a "ph" which I am not aware was ever the case in pure Welsh orthography. On the other hand, this tomb from 1853 refers to Y Felinheli rather than Port Dinorwic. This poor man lost his son and his wife within a year. |

|

The stones usually tell you simply where a person was from, what community they belonged to. There is generally no reference to professions/trades, nor did I see any references to Bardic names, though they could have been there. One of the exceptions is this memorial to the Station Master in Conway Valley, which also includes his parents who followed him 22 years later. |

|

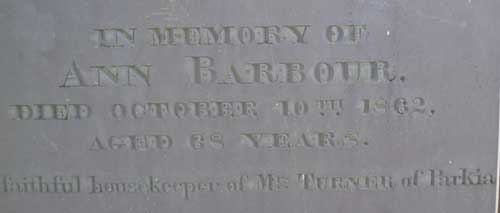

This is a memorial to a lady who relied on the beneficence of her boss to ensure her earthly repose. |

|

Quotes both from the bible and from literature abound. This quote is from Robert Williams Parry's lament for Hedd Wyn from Trawsfynydd who was posthumously awarded the Bardic Chair at the Birkenhead Eisteddfod in 1917, some 7 years before this 75 year old was born: the journey of life has come to its end." |

|

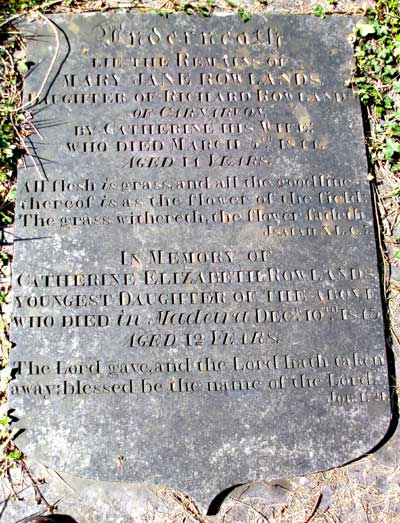

This is a tantalising inscription. It commemorates the death of the 14 year old daughter, by this wife, of Richard Rowlands of Carnarvon, and the death of his youngest daughter who died in Madeira. The question is what was he doing in Madeira and who was the mother of his youngest daughter. And then the very neutral observation: |

|

And sadly, some are still dying young. "Missing your rearing and watching you grow up." |

|

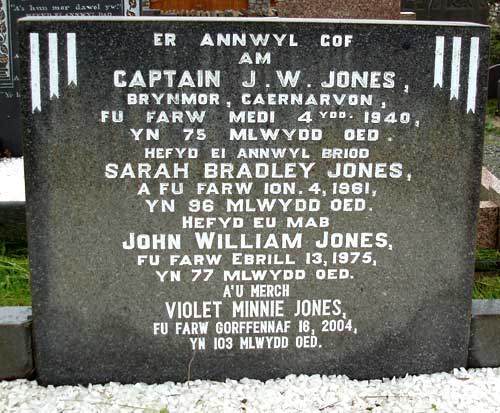

At the other extreme, Violet Minnie Jones lived to 103, and the average age of herself, brother and parents was 88. Some people benefit from the sea breeze! Mind you, the women in this family well outlived the men with an average age of 100 compared with 76 for the men.

|

|

Some not only break the slate mould, they marry into other celtic tribes. Sarah Ellen, daughter of Capt. William Evans, appears to have married the Scot Simon McLeod, far away but never forgotten. |

|

Some went even further afield to find a spouse, or did the spouse come to them. Grandson Paul Stuhlfelder still lives in the area - according to MySpace. |

|

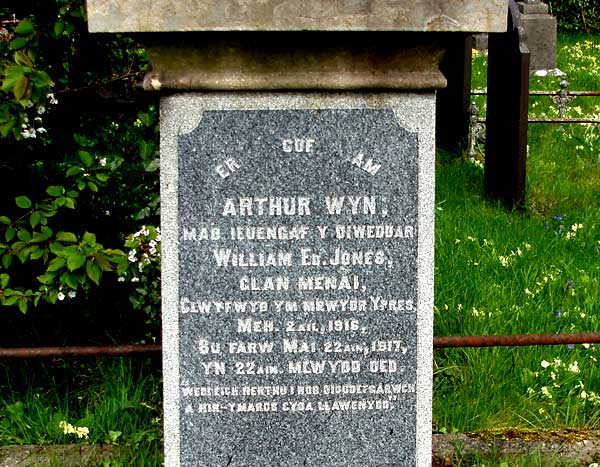

And yes, WWI has touched everywhere. The wounded get buried at home if they live long enough. The fallen are as likely to be a name on a wall with thousands of others in the foreign land in which they fell. Arthur Wyn Jones, wounded in the battle of Ypres in 1916, died a year later, buried in his home churchyard. John P Dwyer, died in the assault on High Wood on the Somme, 1916. Lies in the muck where he fell. His name on the monument at Thiepval. |

|

And will this generation continue to pay their respects and their contributions? The graveyard is currently quite well kept and many of the inscriptions show signs of renewal and maintenance over many years. The air is one of care, concern and respect. The notice above, and its condition, would make you a little apprehensive about the future. |