Lady Chatterley

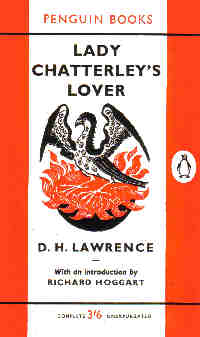

I was working for British Railways in Jersey in 1961, just after the big court case over the publication of the Penguin edition of D H Lawrence's Lady Chatterley. Whatever about access by the ruling and literary classes, the idea of mass access to this alleged pornographic novel by the working classes excited the British Establishment beyond belief. The trial was long and arduous. I remember, Roy Jenkins was called as an "expert" witness, whatever that meant in the circumstances. In the event the book was passed for publication and the vulgar masses, including myself, descended on W H Smith to purchase our share of the upper class orgasm. For me the context was simple. The Ireland of the time was an extremely repressive and illiberal society, at least in terms of overt sexual mores. The list of banned books would be incomprehensible to a modern day readership. I am the proud possessor of an import licence for: Candy, The Dark, 1984 and Borstal Boy - all banned under the obscenity schedule. This was initially refused but subsequently granted following representations made on my behalf. I also have a permit to import All Things New by Anne Biezanek, which was banned under the contraceptive schedule. This book recounted the difficulties experienced by a Liverpool lady with the Catholic Church when she attempted to set up a birth control clinic in that city. It also listed the extent of discrimination against women by the Catholic Church through the ages.

For me the context was simple. The Ireland of the time was an extremely repressive and illiberal society, at least in terms of overt sexual mores. The list of banned books would be incomprehensible to a modern day readership. I am the proud possessor of an import licence for: Candy, The Dark, 1984 and Borstal Boy - all banned under the obscenity schedule. This was initially refused but subsequently granted following representations made on my behalf. I also have a permit to import All Things New by Anne Biezanek, which was banned under the contraceptive schedule. This book recounted the difficulties experienced by a Liverpool lady with the Catholic Church when she attempted to set up a birth control clinic in that city. It also listed the extent of discrimination against women by the Catholic Church through the ages.But I digress. The point is that nobody of my ilk would ever pass up the opportunity of buying "dirty" books to bring home from England, or wherever. That would have been a mortal sin of a different kind. So, I found myself in Jersey with my copy of Lady Chatterley. It really was the most boring book imaginable, except for one or two pages around page 100 as I remember, but it now had a cachet, a pedigree and I was determined to bring it home with me.

Rather than try to hide it, I flung it on the top layer of my suitcase, in a fit of bravado, and set sail, literally for home. It must have been the guilty look, or what is now described as victim posture, that provoked the Customs man to open my case, where he immediately found the offending piece of literature. He didn't say a word, just took it and put it to one side. I was mortally embarrassed and glad to escape with my life. I said nothing, gathered my belongings, and, figuratively speaking, ran.

Rather than try to hide it, I flung it on the top layer of my suitcase, in a fit of bravado, and set sail, literally for home. It must have been the guilty look, or what is now described as victim posture, that provoked the Customs man to open my case, where he immediately found the offending piece of literature. He didn't say a word, just took it and put it to one side. I was mortally embarrassed and glad to escape with my life. I said nothing, gathered my belongings, and, figuratively speaking, ran.All was well until a fortnight later I got a letter from Custam agus M�l, telling me to report to their offices in Parnell Square, in connection with a customs matter. I was shattered. Would I be the centre of an Irish version of the English penguin trial. What would the Mammy say, think.

Quaking, I appeared at the customs office. To my relief I was simply required to observe the customs officers open a parcel addressed to me from my landlady in Jersey enclosing a tape recorder lead I had left behind. She had forgotten to put the green customs sticker on the parcel and they were not entitled to open except in my presence.

A close shave with ignominy, or literary fame, who knows.

Casement

While on the subject of banned books, I remember the publication of the Trial of Roger Casement in the Penguin series of famous trials in 1964. The book was written by H Montgomery Hyde, an Ulster Unionist, who would not have been judged objective on the matter in this part of the country. The distinctive feature of this particular book was the publication in an annex of explicit extracts from the diaries. Fred Hannah devoted a complete window display to the book, a copy of which I snapped up on the basis that it would probably be banned, which it was in short order.Blanshard

In UCD I did a primary degree in Economics and Politics [Group IXA]. Maurice Manning was my tutor for politics and in the context of the study of pressure groups and the dynamics of political power in Ireland he recommended that we read Paul Blanshard's The Irish and Catholic Power. This book was a sort of internally banned book in the UCD library. The librarian, Mary Ellen Power, a formidable lady, had it stashed on a special shelf and you needed a note from your tutor to get hold of it.It was a revelation. Blanshard's purpose in writing it was to show how the Catholic Church controlled almost all aspects of religious and secular life in the the Republic, and it contained an absolute treasury of material, enough to blow the mind of any ordinary but curious catholic in the Ireland of the day.

Blanshard explained that the book had been written in response to a kind of challenge. Apparently, Paddy Lynch [correct me if I'm wrong] had claimed in the magazine Studies, that Ireland represented the perfect marriage between the State and the Roman Catholic Church. This was in response to some criticism of intolerance by the Portugese Catholic Church of attempts to create a secular society in that country.

Blanshard explained that the book had been written in response to a kind of challenge. Apparently, Paddy Lynch [correct me if I'm wrong] had claimed in the magazine Studies, that Ireland represented the perfect marriage between the State and the Roman Catholic Church. This was in response to some criticism of intolerance by the Portugese Catholic Church of attempts to create a secular society in that country.Blanshard claimed that far from being the perfect marriage, the Irish situation represented the furthest the Roman Catholic Church was prepared to go in making concessions to the secular state.

The book is extremely well written, the research thorough and the language moderate. He was writing for an American audience and he proved his case beyond reasonable doubt. A few particular images from the book remain with me.

A photo of a protest parade with a big banner which read: Don't nationalise the national schools. This would presumably be unintelligible to foreigners, but you have to remember that in Ireland the "national" (ie primary) schools, while subsidised by the State, were owned and run by the clergy. The banner was in fact a plea to retain religious ownership and control of the nation's primary schools.

Another bone of contention for Blanshard was the status of the Vatican, a sovereign State when it suited and not when it didn't. This is one that has not been resolved to this day.