SUB ROSA

INTRODUCTION

There I was, happily blogging away on the early days of the EBRD, when the awful thought hit me that I might be taking a lot of this stuff with me to the grave. So I figured I should try and record some of my other impressions of the Bank and its origins before my anecdotage leaves me and I have difficulty remembering my own name.

Note: I'm referring to the EU throughout for simplicity and for the modern reader but at the relevant time there were only 12 members and it was known as the European Community (EC). They were the six founder members France, Germany, Italy, Luxemburg, Belgium and Netherlands (1958), UK, Ireland and Denmark(1973) Greece (1981), Spain and Portugal (1986).

BACKGROUND

Attali: my part in his downfall

(with apologies to Spike Milligan)

I should probably start by explaining where I fit in and how I came to be involved with the Bank from the very beginning.

I was on the EIB desk in the Irish administration when we learned, in late 1989, of Jacques Attali's plans to set up a new development bank to help in the transition of Central and Eastern Europe and the USSR itself to the market economy and rule of law.

It was sort of assumed that this would be along the lines of the EIB and that's why it landed on my desk. There was some scepticism initially about the need for a new bank as EIB was already operating in Central Europe, but that bank sort of went to ground in the face of the combined forces of Attali and Mitterand and so a new and specialised bank was on the cards.

I was then involved in the negotiations in the first half of 1990. Ireland had by then taken over the EU presidency from France but the EBRD project remained a French one. It was, after all, to be one of Mitterand's "grandes oeuvres", but Ireland did play a central role as the project was seen as coming out of the EU and that Community was to have a majority shareholding.

Subsequent to the signing of the Bank's Articles of Agreement by member states in mid 1990, there followed a year of interim activity while the Articles made their was through the various member states ratification procedures. During this time a "shadow board" consisting of representatives of the member states was assembled to negotiate relevant policy and procedural documents which could all be endorsed at the first meeting of the Bank proper, and so the project would hit the ground running.

When the Bank then formally came into existence in early 1991, I was on the Board as an Alternate Director for the first year of it's existence.

During all this period I was still on the EIB, and now also the EBRD, desk in the Irish administration and I remained there until 2000 when I transferred from international financial institutions to domestic expenditure control.

BEGINNINGS

Attali's "Grande Oeuvre"

Central and Eastern Europe had been evolving towards a more market economy and the USSR had its glasnost and perestroika, so there was a big shift happening in that region. We already had the African and Asian development banks as part of the Bretton Woods structures but there was no bank which had this region as its sole area of operations.

Attali, who was Mitterand's chief advisor and the French Sherpa at the G7, saw the opportunity for a serious stroke and convinced Mitterand to run with it. At least that is my understanding. It suited the French, where there was a tradition of "grandes oeuvres" and it would also ensure their influence in this newly evolving region.

The first reaction to the suggestion in many EU member states was that surely the EIB, which was already dipping its toes in this water, could do the job. I think there were two reasons why this didn't come about.

The EIB was, even at that stage, very much a bricks and mortar development bank and its approach was always prudent and generally conservative. This was necessitated to some extent by its financial structure and leverage. But the ethos was a traditional one and lacked the sweep of the French proposal.

Attali, and by extension Mitterand, had already become infected by the lure of a totally new bank with fully international membership (eg as in OECD) which would concentrate on this new area of operation and bring with it all the latest best practice and enthusiasms.

So the EBRD was born, on the lines of the African and Asian development banks, but in starting from scratch is would avoid the legacy issues of these banks and would also have the possibility to import best practice from a host of public and private international institutions. And I have to say that this is precisely what happened.

THE PARIS NEGOTIATIONS

USA gets its oar in

The first negotiating meeting took place in January 1990 in Paris. The tone was set very quickly. Attali did not like an intervention by the USA negotiator and made a remark to the effect that the USA was a guest at this meal and implied they should defer to their host. The USA delegate was in like a shot to remind Attali that he was a paying guest.

This USA/Europe split was there right through the negotiations. The USA saw itself as a champion of democracy, human rights and the market economy, and by God, was it going to make sure that those pesky Russians and their sattelites knew it. The European approach was more nuanced and, while supporting these aims, knew that structures which had taken time to build in the "west" could not be imposed overnight on the countries of operation. The USA approach seemed to be that you could drop this stuff from a flight of B52s one night and the place would wake up a democratic market economy the next morning. There was also a diffence of approach regarding the State sector. The USA saw no place for it in this operation. This was about supporting privatisation. The European approach allowed that this required an infrastracture which was not in place and which States would need to be supported in setting up. The eventual articles reflected a compromise on this.

One of the issues that rankled with the USA was the proposed full participation of the Soviet Union in the Bank, I mean as a shareholder and not just a recipient. Attali was anxious for the widest possible membership and he would probably have been supported in this by most of the Europeans. However, for the USA, Soviet participation, even as a recipient, was a bit like inviting the devil to dinner. They didn't like it, but if it was to be, then they would sup with the longest spoon available. This resulted in some very restrictive clauses in the eventual Articles, whereby in the initial years the Soviets could not benefit from the operations of the Bank beyond the amount of their initial paid up subscription, in other words not at all financially.

It might sound flippant to mention sandwiches at this point. But it isn't. At the initial meeting the delegates were provided with refreshments in the form of soggy sandwiches. Partly as a result the afternoon session took on a bitchy atmosphere. I don't think we saw another sandwich. Elysée catering was henceforth laid on and spirits improved enormously. This resulted in me really regretting our Presidency role. Had I only been Ireland I could have relaxed as we did not have any really serious issues to pursue in the negotiations and I could have indulged myself (a little). As it was, if any one of the EU members had a problem it was in part our problem and the whole thing was really a roller coaster for us. So it was loads of adrenalin rather than gelled prawns and the best of wines for lunch.

Delegation and the problem of time zones

There were many tense moments and much behind the scenes activity. You have to remember that, while this was a new bank starting from scratch, the members had different legal systems and legacy issues and progress at times was excruciatingly slow. Even something as apparently trivial as time zones could slow things down. For example, the Japanese delegation seemed to have very limited delegated authority and everything had to be confirmed with or approved by Tokio. This effectively meant lots of overnight scrutiny reserves and people often didn't know where they stood until the following day or sometimes even later.

No Reds under this Bed

Apart from the "big issues" of Presidency, location and currency, the abiding rift was between the European and USA conceptions of what the Bank should be. The USA were ideologically opposed to the bank getting involved in supporting the state sector in its countries of operation. After all, wasn't that what was wrong with the communist system in the first place, excessive centralisation and state control. The Europeans were much more relaxed about this and, even going on the example of their own countries, felt that state underpinning for much of the Bank's proposed operations were essential. This applied to both physical, say transport and communications, infrastructure, as well as to the establishment of a financial sector and market operations which would be a new development in the Soviet Union.

Innovation posed linguistic challenges

In fact the degree of innovation involved in the Bank's very establishment was brought home vividly during the preparations for the signing and ratification by the members of the agreed Articles. The linguistic challenges alone were enormous as some of the western European concepts had no equivalents in Russian and a new vocabulary had to be invented.

Just as an aside, I would be very familiar with this sort of problem in the Irish context. The evolution of the financial and technical world has been expressed largely through the English language and as a part-time translator I am often faced with having to either compose or make a call on Irish language equivalents. The French have also had this problem, particularly since the 1960s when these developments accelerated dramatically, but they have gradually assimilated or translated evolving terms, such as starting with "tableaux entrée/sortie" and ending up with "tableaux input/output". In the case of the EBRD and the Soviet Union it was a case of one huge culture shock coming all at once.

Attali's bid to hold on to EU Presidency

Although, as I said, the EU presidency passed from France to Ireland at the beginning of the negotiations and we, the Irish, were chairing the EU coordinating meetings, Attali had a clever strategy in his attempts to maintain control of the EU presence. He made a point of inviting the heads of EU delegations to very posh dinners where, as host, he was accorded some deference which he exploited to the full. It was when my boss was unable to attend one of these that I got dragged in and had an exclusive "working dinner" with my "betters" where I found myself under extreme pressure, particularly from Attali, who wanted to manipulate the agenda of the upcoming Ecofin. That, of course, was ultimately a matter for the EU Presidency, for which I was the proxy on this occasion.

.

A President in Paris

The two major outstanding issues in the negotiations at that stage were who would be President (Chairman and CEO) of the Bank, and where would the Bank's headquarters be located. At an early stage the French had made a pitch for both, but, as we now know they got the Presidency and the UK got the location. These questions had escalated during the negotiations and were the subject of correspondence at Prime Minister level. So they were very hot.

At that posh dinner, Attali was trying to force these two issues onto the agenda of the upcoming Ecofin on the following Monday. He decided to do a tour de table at the dinner and as he went round the table I experienced a rising wave of panic. The negotiators were not opposing his request and I was Mr Ecofin for the night. He seemed to be having it all his own way until he reached the last on his list, Nigel Wicks, UK Treasury Secretary. Nigel piped up that he had no objection whatever to these matters being raised at Ecofin. At this stage I was in a state of internal collapse. Then Nigel added the rider that his response was subject to London being the agreed location of the Bank's headquarters. Nice one Nigel. So when Attali then came to me I was able to make the point with confidence that these matters were now being handled at Prime Minister/Head of State level and that it would not be appropriate for them to be raised at the forthcoming Ecofin.

Who and where?

The two issues concerned, which were the highest profile ones and the last to be resolved, had a very interesting path through the negotiations. As the French were running the show it was clear that many of the delegations would feel morally obliged to recompense them in some way, most likely by voting for France's candidate for Presidency or location. This was a tricky area. The Presidency would be transient. The country which got it first would not necessarily retain it subsequently, while the location would be permanent. The French had lobbied for both, with Paris as a location and Attali as president. It then struck them at some stage that pitching for the two could split the gratitude vote and they might even end up with neither. So which was it to be? The location, which I suspect would have been the French Treasury's preference as it would bring some permanent benefit to Paris and the French economy, or the Presidency, which would be transient but would translate into a personal reward for Attali. No two ways about it. The French immediately dropped their pitch for Paris, and even denied they had ever entertained it despite having circulated promotional documentation to the negotiators. Clearly Attali was not letting go, regardless. In the event he beat his nearest and only rival, the Dutch Finance Minister, by a wide margin. During the voting at the final session, he relinquished the chair and left the room, as he was a candidate. All right and proper. But when the result was announced he swept back into the room with his retenue in a show of triumphalism that would have done credit to Louis XIV. It was pretty tasteless and made a lot of those present uneasy, but there you are.

That was the Presidency settled. Then there was the matter of the location of the Bank's headquarters. London won that vote and the British had at the back of their mind that the Bank would be one of the anchor tenants in Canary Wharf, a dockland area which was fast developing into a financial centre. They were even prepared to provide a significant financial incentive to the Bank to locate there. So the chips seemed to be falling into place. To their horror, Attali then refused to go there. It was the City of London, the real financial centre, or nothing. And he got his way, Leadenhall Street just down the road from the Bank of England.

EU almost comes of age

There was huge enthusiasm among the EU member states as the negotiations progressed. The ECU at the time was based on a basket of currencies but it was being used as an accounting unit in most of the EU's internal financial activities. It was the firm intention of these EU member states that the capital of the Bank would be denominated in ECU. While that did mean that subscriptions in the member states own currencies could vary from what they thought they had subscribed to, the use of the ECU was seen as representing the entry of the EU onto the world economic stage in some way. Needless to say the USA was bitterly opposed to this and proclaimed loudly that there was no way Congress would sign up to subscriptions in a "floating currency". Clearly from their perspective the dollar didn't float! Anyway, as this turned out to be a make or break issue for the USA and as Attali was desperate to have them on Board, the EU eventually backed down and members could choose to denominate their subscriptions in a variety of ways, including in their own currency. My recollection is that the EU buckled at a coordination meeting at the Chateau St. Cloud.

St. Cloud, pray for us

As far as the St. Cloud meeting was concerned, the French secretariat had issued an edict that only one member per delegation would be allowed at that meeting. This was supposed to operate like the original concept of the European Summits. In that case it was thought that, if you locked up all the heads of state and government in a room with no advisors, they would have to work out some conclusion to the outstanding problems of the day and, having committed themselves, could not then allow their advisors to question the outcome. This had worked up to a point at EU level but eventually advisors became included and then thing just became another conventional layer of the administration of the EU.

Anyway the French edict on St. Cloud led to howls of protest from some delegations. I well remember the Italian delegation turning into a state of civil war. The Treasury claimed precedence and was going to attend but the Foreign Affairs Ministry didn't trust the Treasury and kicked up an enormous fuss. The Danish delegation had a problem as they were three divine persons in the one God. The Treasury, Foreign Affairs and Prime Minister's Departments all claimed equal status. Now, the French had made this rule unilaterally, as far as I am aware, and then put it up to the Irish Presidency to enforce it. In the event it proved unworkable and I recollect personally conceding to the case made by both the Italians and the Danes. My colleagues may have come across other examples. Anyway the edict was unenforceable at the end of the day.

The Special Relationship

I suspect future historians may end up overestimating the effectiveness of EU prior coordination in these negotiations. Yes, every plenary meeting was preceded by an EU coordination meeting but while these were useful they often as not reached no conclusions except occassionally at expert level. The British were a major problem. I mentioned the significant differences in the conception of the Bank between the Europeans and the Americans. Well the British had this "special relationship" with the USA and protecting this often took precedence over achieving an EU consensus. I lost count of the times, when intervening at the plenary session, I could not put an EU view, but had simply to state that the majority of EU members felt such and such. The only consolation in this was that most member states did not then need to individually state their views in plenary and that may have saved us some time. One wonders at the quality of the "special relationship" even then but I suppose that is something outside my remit on this occasion.

EFTA strikes back

One group among the negotiators did, however, think the EU coordination meetings were for real and gave the EU an unfair advantage. That was the EFTA group led by Austria, which was not then a member of the EU. EFTA was now quite a small group. Originally set up by the UK when it was refused entry into the EU, they were abandoned by the UK in 1973 when it finally succeeded in getting into the EU. Heiner Luschen was the Austrian delegate and he set up a rival EFTA coordinating group. We sometimes ended up exchanging dark glances as we passed in the corridor. If only he knew how tame the EU coordinations really were. As a footnote I should mention that Heiner subsequently became a member of the Board of the Bank and served the Board very well as its conscience when Attali tried to railroad stuff through. But I am getting ahead of myself now.

Why couldn't EIB do the needful?

As I mentioned earlier, the EIB avoided attempting to fill the space that subsequently became the EBRD, but the EIB did take part in the negotiations and ultimately became a shareholder along with the EU itself in addition to the individual member states. The EIB were very anxious to have a seat on the Board of Directors and there was constant pressure, mainly from those members outside the EU, to bump them off. The EIB negotiator, Ernest Günther Bröder the President of that bank, despite having a seat at the negotiating table, chose not to engage in open negotiation and confined his efforts to background lobbying. This meant that he had not spoken at the negotiations except at the very end to thank everybody for their cooperation. As soon as he piped up, Attali was in like a shot - le fantôme parle, the ghost speaks, which gave rise to merriment all round.

Participation by the EIB in the Bank was by no means a foregone conclusion. There was a potential conflict of interest as EIB was already operating in what was to become the terroritories of operation of the Bank. In fact, at one stage, the Japanese sought clarification on whether the EU as an instution could participate. You have to remember that it was the EC at that stage and it was not clear to everyone that it had the required legal personality to enter into this type of deal. It fell to us as Presidency to sort that one out.

At the end of the day the EIB not only participated in the EBRD as a normal shareholder, it assisted it financially and in other ways in setting up the operation.

Bedfellows: Charlie Haughey and François Mitterand

I remember an occasion towards the end of the Paris negotiations during the final discussion on the Bank's remit when the inclusion of insurance being listed among the Bank's instruments came up. The Belgians, and only they, seemed to be having some intractable problem with this. Now I knew my prime minister figured he had the inside track with President Mitterand and I decided to see if I could use this in any way to get over this hurdle. I approached my Belgian colleague and made it clear that my prime minister as EU Presidency at the time would not be pleased and that he might have bring this to the attention of President Mitterand, with whom he had a special relationship. "What, yours too?" was the unfazed reply from my colleague. It was then that I copped on to one of Mitterand's tricks. He gave other leaders the impression that their access to him was privileged rather than shared and I'm sure this served him well over the years. It certainly did in the case of my prime minister.

A Tower of Babel?

There are a number of points I could make about languages and one funny incident. The eventual plan was for there to be four working languages in the Bank, English, French, German and Russian. While it was clear that a lot of stuff would have to be provided in the official languages of the member states, having all these languages in use for Board meetings and Board documentation at the London HQ would have been an enormous inconvenience and very costly. So it was agreed that the four mentioned above would constitute the actual working languages of the Bank in London. At a late stage in the negotiations, the Russian and German speakers said they would concede a single working language (presumed to be English) if the others would agree. Attali immediately took off his Chairman's hat and put on his French beret (figuratively) stating that there was no way the French could countenance this unless the single language was French. That put paid to that, so the Bank (presumably) still has four working languages.

I was quite amazed that the others, bar the French, were prepared to concede a single working language. Had I had more international experience of international financial institutions such as the IMF and World Bank, both with HQs in Washington, I might not have been so surprised. Remember I was on the EIB desk and that bank is structured quite differently from the Bretton Woods institutions, responsibility for which I only took on at a later stage.

However I did have one experience during the negotiations which should have alerted me. The original negotiations were held in the Kléber Conference Centre in Paris, and because the EBRD had come suddently on the scene and the negotiators' diaries were already almost full, the meetings tended to take place over weekends and go on late into the night.

One night I was chairing an EU coordination meeting when the clock struck midnight. Anne le Lorier, who was sitting by my side, whispered "thank the interpreters". I asked "Are we winding up?" "Never mind" she said "just thank them". So I did. And what next? Apparently we were now to continue without them. Fortunately, though I had never expected to be in this position, I had actually read the excellent Presidency Manual prepared by our own Department of Foreign Affairs. The one thing that now screamed at me from that was "Never say 'we will continue in English'" as this will get up a lot of people's noses. What you were supposed to do was apologise for the lack of interpretation, reiterate that we were working in a very tight timeframe, and simply suggest that we should try to continue, without, if possible mentioning the word "English". Which advice I followed and was amazed that the meeting just continued as before but wholly in English. I was floored. It was only afterwards that I realised that the level of the people I was dealing with, and their briefs covering international financial institutions, meant that most of them had done a stint in Washington and I needn't have worried. That meeting didn't finish until 2am.

Mind you, what most of them had was not exactly the Queen's English, more the American variety. But never mind, I had no trouble understanding that dialect.

Those damn frenchies.

I remember one amusing incident which occurred during the later negotiations and which involved the two versions of English.

Attali, at one stage, was becoming very impatient with the delegates' preoccupation with details, particularly the financial ones, which he felt was obstructing his own personal efforts to advance the European project.

We had got to discussing the financing of the Country Directors' Offices when Attali finally lost patience and had a go at the delegates in a fine burst of French invective. I caught the eye of one of the UK delegation and had to look away. I then noticed that virtually all of those who were following the English language interpretation had lowered their heads and were trying to avoid eye contact with each other.

The English language interpreter had just had Attali say: "We are here trying to create a new European Institution and you are arguing about the price of the furniture and the quality of the typewriters. Next thing you will be disputing the size of the rubbers!"

Thank God, I thought to myself, for a taste of the Queen's English for a change. But you can't be too careful

Me and Mikhail Gorbachev, NOT.

I nearly didn't meet Mikhail Gorbachev. It happened like this. I had just returned to Dublin after a few days long session in Paris. Attali meanwhile decided he had to meet Gorbachev in Moscow for some reason or other. However he clearly wanted EU Presidency cover and issued an instruction to my boss's boss that he was to accompany him to Moscow. This involved leaving Dublin more or less straight away for Paris and turning up at a military airport on the outskirts of the city at midnight to fly to Moscow. As it turned out nobody in Dublin was prepared to go so Attali went alone and, as far as I know, didn't actually succeed in meeting Gorbachev. I mention this particularly as it illustrates how Attali could conjure up a French military jet at will as it were. He was used to doing this and it was part of what led to his downfall when the Bank eventually located in London and his normal method of air travel became privately hired jets.

LANCASTER HOUSE

Interim doodles

As I said, the negotiations at the intergovernmental conference took place in the Kléber Conference Centre near the Arc de Triomphe and in the exclusive 16th arrondissment. Attali was always one for the flamboyant gesture and maximum status.

Well, the meetings of the "shadow board" in 1990/91 took place in London, which had been decided as the location of the Bank's headquarters (and that's another whole story). Nothing less than Lancaster House, the scene of many historic negotiations, would suit Attali and he got his way.

President elect Attali

Again he was keeping his grip on the EU members by inviting them to lunch. One of these occasions was in the Meridien Hotel in Picadilly. This was within walking distance of Lancaster House. Attali made a little speech before the meal, reminding us that this was his brother's hotel. (His brother Bernard was the head of Air France at the time and that airline owned the Meridien). I remarked that I hoped he would not be dishing out contracts at EBRD on the same basis as he chose his hotel and that remark turned out to be a brief conversation killer. But it clearly struck home as on the walk back to Lancaster House a senior member of his cabinet caught up with me and said the President would like me to be reassured that tendering for contracts at the Bank would be dealt with by the book. I am sure that has since been the case, though one of Attali's first appointments at the Bank was an actual French chef.

Diplomatic immunity

Another question that was on the table in Lancaster House was the question of diplomatic immunity for Bank staff. In the old days this would probably have been an automatic entitlement for Board members of an international institution if not for the bulk of the employees of the headquarters staff. However, there had been a lot of abuses of this privilege since those days and at the time the Bank moved into London there had been public rows over the employees of certain embassies parking their cars all over the place and then claiming diplomatic immunity when ignoring the parking tickets. I'm sure some people ended up disappointed, but my recollection is that immunity was only granted to the President and possibly the Vice Presidents and, of course, such immunity could always be waived by the Bank itself. As far as I remember the records, communications and property of the Bank do have a measure of diplomatic immunity wherever they are situated.

INAUGURATION

You can skip this section if you've already read it in the blog.

Mary Robinson's hunger

Then there was the inauguration of the Bank in London in 1991. This was a very big splash and in the course of it Attali organised a working lunch for Governors. Albert Reynolds, as Finance Minister, was Ireland's Governor and was the approriate person to attend the working lunch.

However Mary Robinson, the newly elected President of Ireland, was in town on her first trip outside the country as President. She had been one of the adjudicators of the Bank's logo competition (Vaclav Havel was another). The logo was being launched at the inauguration.

Attali was very status conscious and preferred to have a Head of State at the lunch rather than a mere Minister for Finance, so Mary was invited instead of Albert.

I put my foot down and reminded Attali's cabinet (Sylvia) that it was a working lunch, that Mary was a non-executive Head of State like the Queen of England, and to cap it all was not the Bank Governor. I said her attendance at the lunch would cause a constitutional crisis in Ireland. So it was accepted that she would get bounced and Albert would be invited to attend the lunch. The entertainment laid on by Attali was the renowned cellist Rostropovich. I'm sure Albert enjoyed that with his background as a dance hall promoter of yore.

My five minutes as Governor

As it happened, after the first day at the inauguration, Albert got fed up with the whole thing and I got a call in the middle of the night to say he wanted to go straight back to Dublin. This was arranged for first thing the following morning.

Now Albert's speech was scheduled for that morning and as I was now Head of Delegation I was faced with either cancelling it or making it myself. As I had written the speech I was loath to see it vanish so I opted to give it myself. The Norwegian Minister, whose speech was scheduled for the afternoon, was also anxious to be gone. He was looking for a morning speaker to swap with and, as I was going to be around anyway, I swapped slots with the Norwegians. That gave me plenty of time to make a few amendments to the speech to insert a few, not too obvious, digs at Attali who had been getting on my wick from a good while back.

I did inform the secretariat of both the swap and change of personnel but the latter never got as far as the captioners in the video room. So the video of me went out captioned as Albert Reynolds, Governor for Ireland. It is now presumably reposing in some archive and may well confuse historians in times to come.

LONDON

London is not Paris

If Attali was the best man to set up the Bank, it didn't necessarily follow that he was the best person to actually run it. I noticed during the negotiations in Paris that Attali seemed to have a very odd relationship with the French press, or maybe it was just that the French press were oddly compliant. On one occasion he had them lined up for a press conference where he expected to be able to wave aloft the agreed terms of the Articles. As it turned out not everyone was ready to sign. So Attali just cancelled the press conference and there wasn't a word about it in the papers the next day.

Then the Bank came to London (a story in itself) and he had the British Press to contend with. They were anything but compliant with this foreigner in their midst. But even before that arose they were mystified. They sent their banking correspondents to interview him and these poor hacks didn't know what to make of this man who kept going on about building a new Europe and so on. I think most of them came to the conclusion that they should have sent their political correspondents instead.

A lofty environmental mandate

Attali was not operating from the same relative power base in London as he had been in Paris and he could not dismiss questions from the press or the public so easily there. At one press conference he boasted loudly that the Bank was the first such international institution with environmental aims and conditions written into its constitution. A diffident attendee asked him politely if the Bank would be using recycled paper. I thought this a reasonable question myself at the time and had formulated an appropriate answer in my head. But Attali hit the roof. Why was he being bothered by such trivial questions when he was engaged in such a monumental work. Bad call.

A permanent fast track

If truth be told, the Board as a body didn't really know what to make of him either. Those of us who had been involved in the negotiations knew his form and nothing he did as Chairman of the Board really surprised us. But there were many Board members encountering him for the first time and were quite taken aback at his autocratic approach to meetings. When they eventually copped what was going on things got into a better balance and the Board took on more of the authority of a corporate body. In the negotiations he could threaten any negotiator who seemed to be getting out of line that he would have a word with their prime minister, which I am sure he would have had no hesitation in doing. The Board came from a wider variety of backgrounds and they were more protected by the Bank's articles and the general codes of corporate practice. The negotiators were much more at the immediate mercy of the political system.

Come into my parlour

But back to the press. At that time the Financial Times was in transition from a purely reporting financial newspaper to an investigative one and it was sniffing around for things to investigate. Attali more or less fell into their lap. He had had the relatively expensive marble in the Bank's foyer replaced with dearer and posher Italian stuff. He flew everywher in a private jet. In the early stages the Bank had spent more on itself than on all of its clients put together. This would not have been seen as anything exceptional at the start-up stage. You need an office before you can start evaluating loan and equity applications. But his obvious extravagance combined with his dismissive attitude towards the press did for him in the end. The press spoke of the "glistening bank", the "bank that says yes" etc. and he became an embarrassment to his political governors.

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Buckets of Buzz

The Bank had one great advantage over many other international financial instutions. It was new and starting from scratch. It therefore had the possibility of avoiding a lot of legacy constraints and of importing or setting up best practice. Also it would be assembling completely new teams. It was a unique mixture of private and public sector in its operations and it had human rights and environmental priorities built into its constitution.

It was a very exciting time, not just for people like me, more or less on the outside, but for the staff of the Bank. There was a great air of excitement and innovation and a sense of participating in a once in a lifetime historic transition at world level. In other words, great buzz.

I was very impressed with how quickly the Bank set about its mission. I find myself saying mission rather than tasks. That is probably an accurate reflection of what was going on.

With the rapid disintegration of the Soviet Union impacting on the field of operations and German reunification impacting on both the countries of operation and the shareholding and management of the Bank, there wasn't time to be sitting around. Things were moving at a frantic pace and people all through the organisation were rising to new, and often unexpected, challenges.

Commuting to the Board

I was commuting from Dublin to Board meetings and I arrived at the Bank one morning to be faced with reacting to a Croatian project that raised serious issues beyond the immediate brief of the Bank. The nub of the matter was are we recognising Croatia as a separate entity. That was not in my remit either and I had to make a quick emergency call to my Foreign Affairs Ministry. After some discussion on this evolving international situation we agreed that I would support the project with its implication that Croatia was now effectively a new state. This was the sort of stuff that was going on all the time and while is was very exciting it was also a bit scary.

Dublin calling

The staff that had been assembled to operate the Bank at that time were very impressive and extremely enthusiastic.

I was working from Dublin and it was a godsend when the Bank decided to set up an online documentation system for Board members and national desks. This was initially hosted by OECD and subsequently evolved into an independent Bank operation. I remember vividly the IT team coming to Dublin to discuss this with us and set us up on the system. Ireland was among the first and most intensive users of the system in the early days. In some small way perhaps a reflection of my own interest in computer technology and my enthusiasm to see the Bank, which I sort of felt was partly my own baby, develop and succeed.

Waterboarding

Another example that impressed me enormously happened at the Bank's Annual Meeting in London in 1997. The Irish Finance Minister, Ruairí Quinn, was Chairman of the Board of Governors for that meeting and in this capacity he would hold a press conference at the end of the meeting. Now the 1997 meeting involved a number of serious cock-ups. The two major ones I remember were that the location chosen for the press room turned out to be a dead area for most if not all mobile phones and the arrangements for registration were such that CEOs of multinationals were left queueing for long periods. There was anger in the air in the press room and Ruairí looked like facing a hostile press mob. The Bank took a ruthlessly professional approach to this. They organised a rehearsal press conference for the Minister and literally tore him to bits. Chairman or no Chairman, they had a job to do for the Bank and they did it. I cringed. Ruairí did well, but was a bit shaken, particularly as he personally shared the criticism of the secretariat and along with the Bank's president had privately bawled out the secretary general at a very tough session the previous day. And so to the press conference. The Chairman took it on the chin. He did apologise for the mistakes that were made but, having survived the earlier ruthless grilling by the Bank's own press people, the actual press conference, tough as it might have seemed to an outsider, proved to be a doddle. This whole incident increased my respect for both Ruairí, who took his grilling by the Bank staff in the spirit in which it was intended, and for the Bank staff who must have been feeling very uncomfortable but showed no quarter in the wider interest of the Bank.

Per omnia saecula saeculorum

I should also mention two issues that came up in the course of my involvement with the Bank - pensions and graduation. The pensions issue arose during the negotiations and the graduation one sometime later, but nevertheless early enough in the Bank's existence.

Some of the member states did find it odd that an institution which had been set up with a specific, and as they thought time limited, purpose should be considering pension entitlements for its staff. It suggested to them that they might be in for a longer haul than originally anticipated. The graduation issue had not arisen at the beginning but as it became clear that some countries of operation were making significant progress there was pressure to prioritise the laggards as far as use of the Bank's resources were concerned. At the same time, no country which was a country of operation at the beginning really wanted to lose the support of the Bank. So the idea of graduation was refined from that of actually leaving the Bank's support to having that support reduced in quantity and applied to higher levels of development. I'm not sure where that stands now as it was only becoming an issue when I left the Bank's desk for other areas in my administration.

Repartee: Attali's comeuppance

In those early days the Bank was struggling a bit to find its way. While it sort of knew where it was going, the variety of situations it faced in its countries of operation and the speed at which things were evolving sometimes made it difficult to know how far to go and to adopt a consistent approach across its range of activities. There was also, in the background, the question of how its activities would relate to and complement other existing international financial institutions which were also getting in on the act. These would include the IMF, World Bank, EIB and some smaller institutions such as the Nordic Bank and Council of Europe funding.

Attali's agenda was unquestionably expansionist. Now that EBRD had been set up everone else should just go away and leave it, and it alone, to do the job. At one stage he proposed using the title "European Bank" for the EBRD but this did not go down well with EIB and it would have muddied the waters for any prospective European central bank. But it was a constant struggle at the Board to try and rein him in a bit.

On one occasion, Tony Faint, the UK Director, who was from DIFID, had a mild go at him, when he suggested that the Bank should give some consideration to what niche might be appropriate for its operations. This was red rag to a bull as far as Attali was concerned and he responded that in French a niche was a kennel where you kept a dog. Tony replied that where he came from a niche was a space that housed the statue of a saint. "Yes, but they're all dead" was Attali's quick retort and that killed that intervention stone dead, so to speak.

You will have gathered that, as Chairman of the Board, Attali liked to have things his own way, and this was beginning to pose a problem for the Board. Every project was some sort of emergency or special priority and was speedily dealt with by the chair. Those of us on the Board who had been involved in the negotiations knew his form. In fact, during the negotiations if he felt someone was getting stroppy he would threaten them with his having a word with their prime minister. However, we were now dealing with a corporate entity with its own constitution. It was operating in the real financial world and the Board had its own corporate responsibilities.

One of the Board's concerns was a feeling that the economic analysis underpinning some of the projects was a bit thin. A result, no doubt, of the speed at which matters were being pushed along. The cudgel here was taken up by the Spanish Director, José Luis Ugarte . He was a nice man with a slightly dry sense of humour. He had a background in economics, in academia and in the OECD, so he was well qualified for this encounter. "Mr President" says he "I think we might take this project a little more slowly and deepen the economic analyis underpinning it". "Not at all." says Attali "Economics is dead. I know. I taught it for years". "Ah yes, Mr President, but that was socialist economics". The Board collapsed with laughter. A beautiful rapier of a sentence. Attali had been socialist President Mitterand's economic mentor over the previous 15 years, even before he came to power. And the Bank was set up to supplant the failed "socialist" economics of the Soviet era. Even Attali had to muster a conceding smile. That, and the American riposte I mentioned earlier, were the only occasions I have seen Attali bettered in repartee, a skill in which he prided himself.

The Macedonian Question

Both Macedonia and Lithuania were in our Board constituency. The Danes dealt with Lithuania and we had responsibility for Macedonia. Macedonia had a language problem with its very name. The Greeks objected to it styling itself Macedonia as they had a large adjacent province of that name whose territory was most definitely not up for grabs. The rule was therefore that the new country had to describe itself as the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, or FYROM for short. This seriously irritated the Macedonians who took every opportunity to travel under Macedonia pure and simple. It was a practice at the Annual Meetings for the countries of operation to produce, in consultation with the Bank, a sort of promo report for possible investors, which would be made available to the public at the meeting. At one stage they produced a cover with "FYR" in six point type under which the name "Macedonia" appeared in mega-point bold type. The Irish delegation advised them that this would not run. Another time they stuck up a Macedonia label on the door of their delegation rooms. This caused another flurry until Tony Brown, the Irish Alternate Director, hit on the compromise "The Macedonian Delegation" which proved acceptable to all.

I should mention that the Irish have great empathy with all countries involved in nomenclature disputes. We have our own share of them and we know that what might appear slight differences, or no difference at all, to outsiders can conceal gross insults between the insiders concerned.

The Macedonian question came to a head at Governor level during one of the Annual Meetings. Strictly speaking each country represents itself directly at Governor level. It is only at Board of Directors level that they are grouped into constituencies under a single director. However, as the Macedonians didn't have a physical presence on the Board of Directors and were not resident in London, it would be expected that the other constituency members who knew the ropes would help them out at the Annual Meetings.

That's how I found myself as an intlocutor between the Bank and the Macedonian Governor during one heated spat. The seating of Governors around the table was arranged in alphabetical order and Macedonia was seated under F rather than M. Their Governor threw a freaker and told me that his Prime Minister was very upset and unless this was rectified by the Bank he would deliver his governor's speech from the public gallery rather than from the lectern. He told me this in the the run up to lunchtime and he was due to speak in the early afternoon.

I rightly felt that the only assistance I could be was to make the secretary general aware of this looming catastrophe and hope he could figure out something. I got him on the phone on his way out to lunch and his response was "send me an email". I knew the Macedonians were serious about this and would have no compunction in carrying out their threat. So I emailed everyone in the secretary general's department in the hope that someone with more influence than me would bring him to his senses in time. They must have, as the matter was quickly resolved, with the Macedonians seated under M but the subsequent printed list would classify them under F.

Nevertheless when the Macedonian governor's turn came to make his speech he appeared at the top of the back stairs, flanked by his staff, and they made an entry down the steps and over to the lectern that would have done credit to the winner of an Eisteddfod chair.

The Nuclear Option

Nuclear power posed a particular problem for Ireland in the context of EBRD. We are a non-nuclear state, although we did consider the civil nuclear option in the 1970s.

Central & Eastern Europe in the 1990s posed a difficult problem for us. We had had Chernobyl, the effects of which came as far as Ireland, and that tragedy, if anything, strengthened the postion of those opposing nuclear power. However, there were many potential "Chernobyls" across the area of operation of the EBRD, some of them held together with sticking plaster, so to speak.

So we adopted what I considered a sensible policy in relation to the Bank's involvement in this sector. The Bank could get involved in supporting increased safety in existing civil nuclear plants. It could also participate in the construction/completion of new, and safer, plants on two conditions: (i) the state concerned shut down corresponding capacity in older very unsafe plants, and (ii) there was no increase in the state's overall civil nuclear capacity. The net effect would simply be to increase the safety of the existing level of capacity. Any new replacement capacity plants would be subject to very strict standards.

Without this scheme, the states concerned refused to close down existing, albeit unsafe, plants. In some cases they relied on these plants for the generation of the bulk of their electricity.

The Bank's policy was an uneasy compromise, but one which, of course, went down well with its nuclear plant producing members. In any event it was being successfully applied in the first years of the Bank, and, initially as a Board member, and subsequently as desk officer I was happy enough with it.

Then, in 1994, Emmet Stagg became Minister of State (junior minister) at the Department of Transport, Energy and Communications, where he had responsibility for nuclear policy. One of his first acts was to decree that Ireland would not support civil nuclear power under any circumstances. If carried through this would clearly effect our stance in EBRD. I explained our position to my minister (Ruairí Quinn) who spoke to the leader of his party, Foreign Affairs Minister - Dick Spring, who spoke in turn to his party colleague, Emmet Stagg, and as a result we were able to pursue our previously existing policy.

I am not up to speed with the latest developments on this front. I know that relations have been difficult and EBRD/EU seems to have been in and out of the scene. There was always competition from Russia to maintain and increase its influence in this sector.

And just for the record, I should say that I hold no brief, personally, for nuclear power. It scares the shit out of me.

OVERSEAS

My four away AGMs

My main travel abroad in connection with EBRD would have been to overseas Annual Meetings. I went to four of these: Budapest 1992, St. Petersburg 1994, Sofia 1996 and Riga 2000.

Budapest 1992

You can skip this section if you have read it in the blog.

The first overseas Annual Meeting was held in Budapest in 1992. The first event of this Annual Meeting, from my perspective, turned out to be the IRA blowing up the Baltic Exchange in the City of London just as I was leaving Dublin for Budapest. So, what has that got to do with the EBRD? Well, the Baltic Exchange is just across the road from the EBRD's then London HQ in Leadenhall St., and were it not for the AGM and the bulk of the Bank's staff being in Budapest at the time, it is likely that many would have been injured, perhaps fatally. As it turned out, apart from broken glass all over the place, only one member of the Bank's staff was injured.

The attack had one immediate consequence for the Irish delegation to the meeting. Our security status was immediately raised to unprecedented heights and the security man assigned to us turned out to be KGB trained. Why the London explosion should have had any implications at all for the Irish delegation in Budapest was not clear to me. But I suppose the Hungarians would not have been up to speed on the nuances of the Irish situation and, in any event, would not have been inclined to take unnecessary risks.

My own initial reaction was how was I going to face colleagues when my countrymen had just almost blown up the Bank's headquarters in London. As it happened, the AGM was attended by the Irish Ambassador accredited to Hungary, Michael Collins, and when I mentioned my concerns to him he was quite firm in his advice. "Hold your head high. They have not done this in your name, whatever their claims." This was a new line of reasoning for me, but as ambassador he must have had to deal with this sort of situation many times, and it made sense. So I steeled myself and took the recommended line.

Our elevated security status following the bombing of the Baltic Exchange in 1992 did provide some amusing incidents.

At one stage, the head of the Irish delegation, Bertie Ahern, then Minister for Finance, had occasion to visit the loo. Our hyperenthusiastic security man preceded him into the convenience and kicked in the door of the cabin to make sure there was no-one hiding inside and to make equally sure that, if there was, he would be in no fit condition to progress his assassination mission. Imagine ...?

Another incident gave the same security man a real fright. It was during lent, and as is publicly known, Bertie is a daily massgoer during this holy season. Well, on the day we were leaving for home, I had arranged for him to attend mass in one of the big churches. Could have been a cathedral for all I remember. Anyway, the security man accompanied the Minister and his Secretary General into the church and kept them under very strict surveillance during the ceremony. This wasn't all that difficult as they were in the one place all the while. Near the end of the mass, the security man, who was beginning to relax and had joined the rest of us at the back of the church, jerked in shock. The mark was on the move. In fact both marks were on the move. He leaped into action and paralelled the progress of the marks up the aisle to the main altar where they received communion and, much to his relief, returned unharmed to their seats. A close call, and a reminder that you are never off duty until the mark is finally out of your jurisdiction.

The following year the Bank's Annual Meeting in London was also preceded by a nearby IRA bomb which which killed a journalist, injured over 40 people and caused £1 billion worth of damage. This was at Bishopsgate near the present headquarters at One Exchange Square. I had heard that this convinced Bertie Ahern that the IRA'a real target was the EBRD. An unlikely thought.

Lithuania here I come

I never went on any Board of Directors' trips as such. I was only on the Board for a year and was not resident in London.

However, shortly after I left the Board, my former Director, Lars Tyberg, arranged for me to accompany him on a trip to Lithuania, which was in our Board constituency. I think he made me some sort of Director's Assistant for the purpose. Anyway it was a very illuminating trip.

We went to two cities. The political capital, Vilnius, where we stayed and where Lars met the President, as far as I remember, and the commercial capital, Kaunas, where the local chamber had arranged a meeting with business people who might have an interest in doing business with the Bank.

Vilnius was very interesting. There was a general look of delapidation about much of the infrastructure apart from a few roads that were of interest to the Soviet Union for accessing the Baltic. There was supposed to be only one hotel up to west European standards and that is where we stayed.

The Matrix

When we arrived to go to our rooms I told Lars I'd give him a call, or him me, and we could go out and have a look around. My immediate problem turned out to be the telephone. Unlike what I was accustomed to, where you simply dialled another room number preceded by a hash, this phone was accompanied by a large folded card, which had a matrix that would put a mega bingo session to shame. Up the vertical axis were the hotel floors and across the horizontal axis the room numbers. Each room, determined by its coordinates on the card, had a unique and unrelated telephone number. It struck me that this PBX looking system should be the first thing to be modernised, but I really couldn't figure how it lasted this long even under an economically inefficient system. It was only when I mentioned this to a few people that I realised how naïve my approach had been. These were all direct lines which went through the local police station.

Tourist dollars

My next surprise was the dual currency system. Everything was priced in both dollars and Lithuanian litas and the combination of pricing and exchange rate seemed to be designed to milk the tourists who were expected to pay for things in dollars. I was poking around a basket of loose postcards in the hotel which were priced in litas. I figured to buy about a dozen to send. The lady in charge of the shop was trying to get me to look at the postcard booklets which were priced in dollars and which would have cost me a multiple of what I would pay for the same amount of loose cards. She was not amused when I stuck with the loose cards.

Ball frames

Then there were the abacuses. I had seen them around in shops, usually beside the tills, and I thought they were either for sale or were some sort of symbol or other. It was only when I made a purchase in a stock depleted department store that I realised they were functional. The assistant totted up the bill on the abacus and then printed a single amount receipt on the cash register. I still haven't quite figured that one out. Whether it was a shortage of paper or some sort of tradition I don't know.

George's bulging wallet

Kaunas was a revelation and showed up what the Bank was up against in its efforts to develop a sustainable market economy in the area. The local chamber of commerce had arranged a session for us with local business people. As Lars explained what we were about you could feel the audience getting very impatient and when he got as far as mentioning business plans he lost them altogether. It turned out they had come expecting cash and had been eyeing George Krivicky's large document carrier with expectant eyes. I don't think I'm being patronising here, but these were people, by and large, who had traditional businesses which were now threatened by new market forces. Their immediate need was for a cash injection to tide them over for the next short while until things would improve. Which, of course, they wouldn't, at least not for most of them. It was a sad encounter.

PEOPLE ROUNDUP

A few remarks on some of the people I encountered

Jacques Attali

Well, the first one has to be Jacques Attali. Funnily enough I was familiar with his name and some of his work as he used to write for Le Monde on economics in the 1970s. I actually included some paragraphs of his in a Government Memorandum on Economic Planning at one stage.

As he was the one who was credited with conceiving the EBRD, he was the one who had to bring it about. To be fair, he was probably admirably suited to this task. He had the most enormous ego I have ever encountered. He was supremely self confident. He knew the international scene very well from his experience in the Elysée and from the G7 in particular. And, he had a wide range of high level contacts in most capitals.

He chaired the intergovernmental conference which negotiated the Bank's charter (Articles of Agreement) and the French negotiating team was led by Jean Claude Trichet, then head of the French Treasury. Needless to say, there was constant tension between what the Treasury saw as France's best interests and how these were perceived by Attali. To some extent this would be normal in any administration but you have to remember that the French President is effectively responsible for foreign policy and thus it tends to be even more expansionary than otherwise, while the Treasury which has to foot the bills would be very much less so. Attali's subsequently becoming Chairman/CEO (PDG) of the Bank also revealed a particular personal interest in the matter.

In his attempts to show his empathy with the various minorities in the Bank's countries of operation he used to say that he himself was a member of two minorities. He was a Jew and he was an intellectual. He never mentioned that he had been born in Algiers as that would have put him in a minority that might not have appealed to his Parisian colleagues. Attali achieved great heights and so did his brother Bernard who became the Chairman of Air France. I always felt there was an element of compensation involved in these great achievements.

Élisabeth Guigou

I first saw Madame Guigou, then on Attali's team and about to become France's European Minister, when she made her grand entry into the initial negotiating meeting in Paris. Every male present saw her enter the room. She was stunning and she had a dress which, as we might say in Dublin, was split up to her oxters.

I subsequently sat beside her at an exclusive dinner in the Raphael in Kléber and I do not remember a single word of the conversation, or even if there was one.

Jean Claude Trichet

Jean Claude Trichet was the lead negotiator for the French. His reputation may have since been a little tarnished from his time as head of the ECB, at least in Ireland, but at these negotiations he played a blinder. It was he who effectively held the whole thing together and it was not easy as there were times when he had to rein Attali in. Not an easy thing to do.

Anne le Lorier

Trichet was ably assisted by the most effective civil servant I have ever come across. Anne was very skillful in her handling of the negotiations and in producing the goods at every session. She was Trichet's right hand person both relating to content and to the running of the secretariat. She got a spontaneous round of applause from those assembled at the end of the negotiations which is more than I can say for Attali. I see that she is now Deputy Governor of the Banque de France and well she might be. Anne has the distinction of being the only person I ever heard using the French past subjunctive in speech, and that was only the once. I don't remember the exact sentence now but I remember noting it at the time.

Pierre Pissaloux

Pierre Pissaloux was working to Ann le Lorier in the Treasury. He was very close to Attali in the negotiations and subsequently became his Chef de Cabinet at the Bank. Like Attali he was also born in North Africa (Tunis). He subsequently made a name for himself in private banking with a strong emphasis on the MENA area.

Miklos Nemeth

I met Miklos Nemeth, the former Hungarian Prime Minister, once and he was present at a number of the Board meetings I attended. He had been instrumental in the fall of the Berlin wall in opening up his frontier with Austria and allowing East Germans exit to the west via Czechoslovakia. He became Vice President in charge of personnel at the Bank. He was a quiet, unassuming, man and I know from a colleague who worked in that area that he was very well thought of.

Clare Murchie

No list of personnel in this context would be complete without mentioning Clare Murchie who was our constituency secretary and who looked after me both as a Board member for the year I was on the Board and as EBRD desk officer in my administration throughout the period from the establishment of the Bank on. She was still looking out for me after I left the Bank desk. I mentioned José Ugarte and Heiner Luschin earlier. Both have since passed away. José died first and Clare suggested I write to his widow, which I did, and recounted her the story I have told earlier. Her reply was most gratifying and I'm glad I wrote. The reply from Heiner's widow was equally gratifying and I was very happy to have shared positive memories of their husbands with these two very gracious ladies. Thanks Clare.

Some Photos

Launch of the negotiation process in the Kléber Conference Centre on 15 January 1990.

[l-r] Jacques Attali: chair of the negotiations and first President of the Bank. Resigned prematurely in 1993 after adverse press publicity. Roland Dumas: French Foreign Minister, subsequently spent some time in jail.François Mitterand: French President and sponsor of the negotiations, involved in his own share of controversies. Pierre Bérégovoy: French Economy Minister, subsequently committed suicide. Michael Somers: Head of Irish delegation and EU Presidency, subsequently awarded the Légion d'Honneur by the French Government.

Launch of the negotiation process in the Kléber Conference Centre on 15 January 1990.

[l-r] Seán Connolly: Finance Ministry Principal at Irish Permanent Representation in Brussels. Pól Ó Duibhir: EIB/EBRD Desk in Finance Ministry, Dublin. Jim Flavin: Foreign Affairs Ministry, Dublin. Maurice O'Connell: Second Secretary General, Finance Ministry, Dublin. Dieter Hartwich: Secretary General, European Investment Bank.

Negotiations in the Kléber Conference Centre on 10 March 1990.

[l-r] Jean Claude Trichet: Head of French delegation. Jacques Attali: Chairman (subsequently EBRD President). : Michael Somers (La Chaise Vide): EU Presidency. Pól Ó Duibhir: Irish delegation. David Williamson: Secretary General, EU Commission. Antonio Maria Costa: Head of EU Commission Economic Service (subsequently EBRD Secretary General). The lady standing at the back is Ann le Lorier.

I remember that particular moment only too well. We were picking up around 2pm after lunch and Michael Somers (EU Presidency) had not appeared. Attali and Trichet were arguing and Costa was trying to get me to make an intervention on behalf of the Presidency. I held out, wisely I think, until the real EU Presidency appeared.

Family portrait at launch of negotiations in Kléber Conference Centre on 15 January 1990.

This is what subsequently came to be known at EU Summits and Ministerials as the "family portrait". It includes just the plenipotentiary negotiators, ie heads of delegations, Madame Guigou, and Attali himself.

Given the numbers involved and the distance from the camera, details from this photo are not the clearest. So I have just picked a few of particular interest.

This is Attali with Madame Guigou.

This is "The Phantôme and the Minister", Ernst Günter Bröder (left) and Vaclav Klaus (right).

Bröder, President of the EIB, was christened the phantom by Attali because he didn't intervene in the negotiations until they were over.

Klaus was another matter. As Attali was going round the table welcoming people to the opening session he came to the Czechoslovak delegation and welcomed some named official. He was met by a slowly and clearly enunciated "My name is Klaus. I am the Finance Minister of Czechoslovakia". This took Attali aback, but only for a moment. Minister Klaus gave us some lighter moments as the negotiations progressed over the following months. He subsequently became President of the Czech Republic.

Horst Köhler, Staatssekretär of the German Finance Ministry, and Michael Somers, EU Presidency. Köhler subsequently became head of the IMF, President of EBRD and President of Germany.

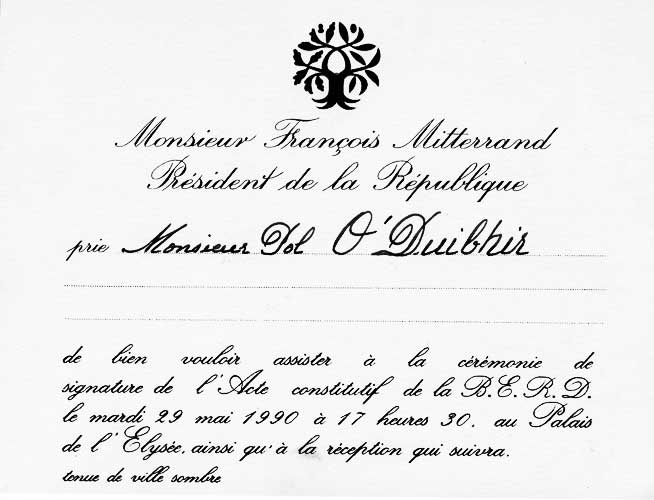

An Invitation

This is the nearest I got to my Légion d'Honneur. François was very nice and appreciated my efforts to sustain the glory of France in the newly emerging market economies to the east. Not quite La Francophonie, but lots of nuclear stations for EDF to play with. And that's as far as it went.

Albert Reynolds had the privilege of signing the document twice, firstly as Presidency on behalf of the EU, and secondly on behalf of Ireland.

ADDENDA

The material below covers things that occurred to me after completing the material above. I will integrate it into the main document eventually but am keeping it separate just for the moment to avoid those who have already read the material above having to plough through it again to find the new stuff.

USA SHARE

The USA insisted, from the beginning, on having the largest individual shareholding in the Bank. I think this was around 10%. I never really figured out what this was all about until much later, years later, in fact, when I finally took over responsibility for the Bretton Woods institutions.

For a state that didn't want to pay in a "floating currency" in case it cost them more than they originally thought, it did not make sense for them to be trying to pay more than anyone else. Their larger shareholding would not really carry with it any material advantage. The likelyhood was that the EU with its majority shareholding would outvote them on any significant issues of dispute and significantly split formal voting in the Board was unlikely to be a regular occurrence anyway.

My subsequent conclusion was that the reasons for the USA seeking the largest single shareholding were:

- it proved a slight PR counterweight to the EU majority shareholding. If USA was accused of being subservient to a European institution, it could at least counter with the fact that it had the largest individual shareholding.

- a hangover from the Bretton Woods institutions, where being the largest single shareholder has significant consequences, namely, the location of the organisation's headquarters. The location of the Bretton Woods organisations in Washington was determined, and is sustained, by the USA having the largest single shareholding in the individual institutions concerned. So defending this over the years has become a diplomatic and bureaucratic reflex for them.

ST PETERSBURG

[You can skip this if you've already read it in the blog post.]

The St. Petersburg Annual Meeting, in April 1994, was a bit chaotic. Different aspects of the meeting were taking place at opposite ends of the city and communications were appalling.

A call came through from Dublin, from Drumcondra. Yes, you've guessed it. Bertie was the Minister for Finance and representing our shareholding interest in the Bank.

As a civil servant I would not normally have had anything to do with the constituency office. But, under the circumstances, I was quite prepared to facilitate contact between Dublin and St. Petersburg.

"Celia calling, can I speak to Bertie."

Now the Minister was at the other end of town and communications, as I said, were appalling. So I offered to relay any message to the Minister.

"No way", sez Celia, "Get him to call me."

So, deflated from my adventurous offer, I set about trying to contact the Minister.

I rang the Bank's administration and was told that the protocol officer was in the building where the Ministers were meeting.

So I rang him on his mobile.

Sez I "Would you ever go into the Minister's meeting and put your phone up to my Minister's ear so I can give him a message."

"No problem" sez he "but unfortunately I am now at the other end of town."

Which just goes to show how us landliners can be foxed by mobiles.

OK. So no go.

The Minister was finally got to ring Celia

.

I learned afterwards that Bertie's car, in Dublin, had been stolen and it turned out that it was only recaptured some days later after a high speed chase down O'Connell St.

Anyway, on this occasion I felt I had stepped outside my proper role to facilitate some people and had been rudely put down.

[I should explain for non-Irish people that Celia, at that stage, was running the Minister's constituency office in Drumcondra. She subsequently became his consort and accompanied him to many events, at home and abroad. The relationship has since broken up.]

SOFIA 1996

I remember three interesting episodes from Sofia. First there was the concert. These annual meetings, and not just of EBRD, usually came with a concert attached. In general these were terribly civilised affairs, usually the best of classical music, proclaiming the civilisation of the country or city concerned to the world at large. Now, I'm not an afficionado and didn't go to all of these. But I went to the one in Sofia and I'm very glad I did.

Instead of the usual classical pieces vying for perfection in their presentation we had a folk night. A pulsating performance of Bulgarian folk music and dancing that would take your breath away and have your feet tapping and your ears ringing for hours afterwards. It was magnificent. And full marks to the Bulgarians for their self confidence. Not that this needs any praise from me. I remember when I was in Bruges in 1967/8 we had a visit from a Bulgarian dance and instrumental troup and they were fabulous. On that occasion, in those cold war days, the troup was accompanied by a heavy apparatchik to ensure there was no offstage mixing between the residents and the visitors.

And speaking of oversight, I remember that it was during this Annual Meeting that my Governor went missing but his security detail didn't. There was a bit of consternation for a while. Could he have been kidnapped under the nose of his security man? Someone would be trouble here. And would we have to pay a ransom? Or would the IRA strap some explosives onto his body and get him to drive a truck into some famous Sofia monument. Didn't bear thinking about.

Anyway, he subsequently turned up unharmed, having purposely given his shadow the slip so that he could inspect Sofia's architectural offerings in peace and solitude. Naughty boy.

And finally, the delegation car. Responsibility for various aspects of the Annual Meeting were split between EBRD and the host Government and all this was ironed out in great detail in advance. Among the facilities provided by the host was a chauffered car for the Governor for the duration of his stay. At least that was the intention, but the wording that year was a bit looose and Heads of Delegation, following the departure of their Governor were claiming use of these cars, much to the embarrassment and annoyance of the Bulgarian authorities.

I had noticed the loose wording in the memorandum of understanding and, though I didn't need a car as the hotel and conference centre were closeby, I decided to test the system and, after the Minister's departure, turned up for the car. The security man was very apologetic. Apparently there had been a problem and the matter was still being sorted between the EBRD and the Bulgarian authorities in what I gather was a fraught meeting down at the Conference Centre. The poor man was very embarrassed, but I assured him it wasn't important and made my way down by foot.

I don't now remember how the matter was resolved as it was of no material interest to me. I think the cars were left at the disposal of the delegations but there was an amount of bad feeling around on both sides. Again, I don't remember but I suspect the memo was worded more carefully for future meetings.

AS GAEILGE

Maurice O'Connell (my boss), Jim Flavin (Foreign Affairs Ministry) and myself did a bit of travelling together to Paris and back for the EBRD negotiations. We needed a team as the negotiations sometimes broke up in to subgroups which had to be chaired as we had the presidency. Seán Connolly (Irish Permanent Representation) was also involved in this but didn't travel with us as he was based in Brussels.

The airport in Paris (de Gaulle) was often a rush for a plane home. The Aer Lingus check-in was usually manned by ADP staff (French)

Anyway, this one day when we were charging for the plane, I was challenged by the ADP lady who said my passport and ticket did not match. This was the last thing we needed - delay. Maurice cut straight across her. "Thats his name in Irish" and almost grabbed the papers out of her hand. Now Maurice can be very persuasive, particularly when he's in a hurry, and even this French lady buckled under the onslaught and handed me back my ticket and passport.

It was only later, when we were actually boarding the plane that we discovered that I had Jim's ticket and he mine. We must have just pocketed the tickets without looking at them when they were handed back to us in a bundle on the way over.

So much for ADP and French airport security. But that was them days and this is now.

TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS OF A DESK OFFICER

I suppose I shouldn't leave this memoir without making some comment on my period as EBRD desk officer, which lasted till 2000.

My successors on the board were a mixed bunch and my relationship with them varied enormously. There were some things that made a desk officer's job easier, and more effective and sharing information was one of these. In some cases I found a carry over from a previous existence, the idea that knowledge was power, which, of course it is. But when you're playing on a team it is for sharing and there were occasions when I very much resented not being fully informed at the outset and then being dragged in at the last minute when my endorsement for some proposal was required, and I had not had time to think it through.

During the first year, when I was on the board myself, I felt a bit like the Blessed Martin de Porres of my youth. You will remember that he was blessed with the gift of bilocation (now presumably trilocation at least following his ascent to full sainthood). I was my own desk officer and that suited me fine. The only problem was the day job and I could not give Board business the attention it merited with the result that an excessive burden was falling on my Danish Director who was full time resident in London.